Introducing :

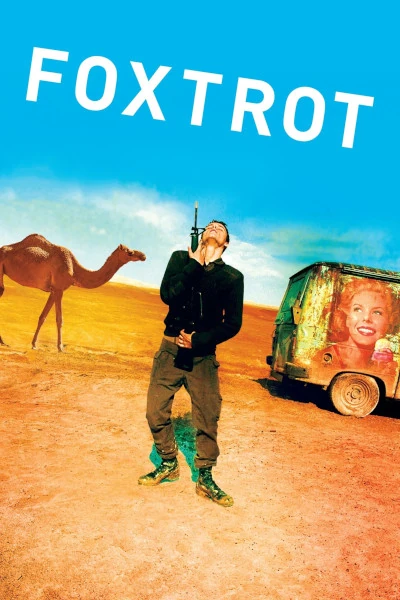

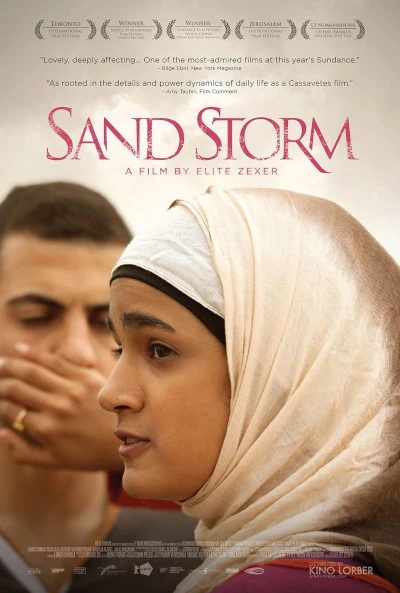

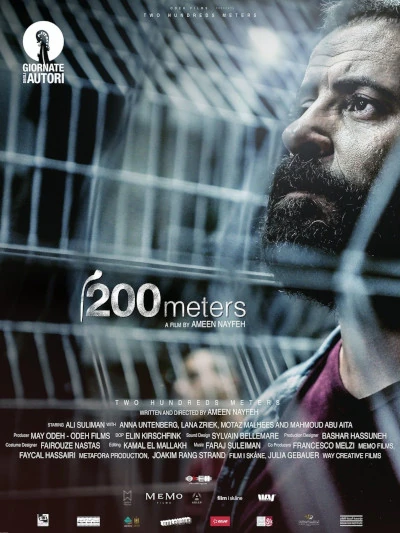

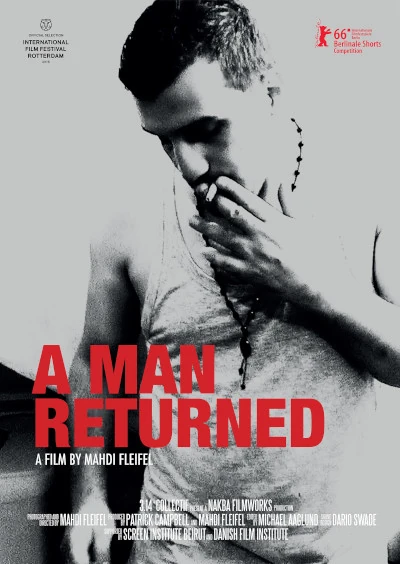

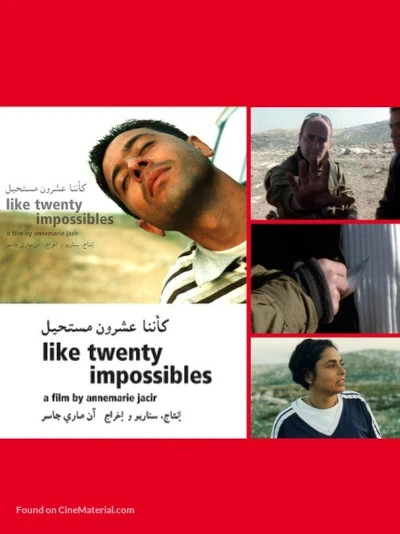

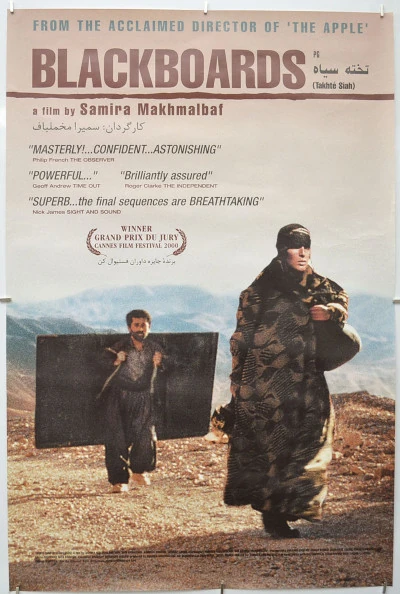

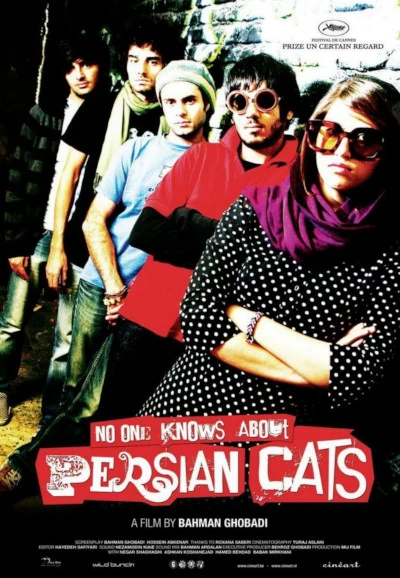

The Arab-Israeli (and Iranian) Film Festival - Watch before the world ends!!!

So it’s time for me to start writing up this project! Let me repeat the basic rule that I set myself - to watch one film from one side, and then very strictly to follow that with a film from the other side.

How did this come about? Approximately two months after October 7th I had a few conversations with friends on both the Jewish and Arab(-sympathising) sides about films relating to the Arab-Israeli conflict, but also films which talk about the problems that are internal to those societies (since it’s true that everything that is wrong with the Middle East does not stem automatically from the Arab-Israeli conflict, albeit that a great deal of it does of course). After first watching two or three Israeli films recommended by a Jewish friend, I thought to myself that I needed to balance my diet, and so I asked around about Arab films to watch.

And then I got obsessed, and started searching, searching, searching on the internet. I can’t honestly remember all the sites that I searched, but I have checked the history on my browser, and found these sites, which should be more than enough for anyone who’s not writing a PhD on the subject (and I most certainly am not doing that):

- Eight films to better understand the Israeli-Palestinian conflict

- 14 must-see Israeli movies (from TimeOut)

- The 10 best Arab films (from the Guardian)

- Israeli war drama films (Wikipedia)

- The Nakba on screen: Five must watch films about the expulsion of Palestinians in 1948

- The 10 Best Movies About The Holocaust

- Top 50 Arabic Movies (IMDB)

- 21 iconic Israeli movies that you must watch

- Ten films to watch about the history of the Israel-Palestine conflict (from Al Jazeera)

- Films about Orthodox and Hasidic Jews (Wikipedia)

- The Best Israeli Films to Watch On Netflix

I followed the one-Arab-one-Israeli rule very strictly for the first twenty or thirty films which I watched, but at a certain point I had to improvise (“cheat”?), because I found a large number of Arab films (many of them Palestinian) on Netflix, and had to binge those before Netflix finally kick me off after my subsciption lapsed. I do have to give credit to Netflix for the large number of Palestinian films which you can find on there, and which will certainly be hard to find anywhere else. A few of them are on display here. I especially want to commend them for presenting a large selection of Palestinian short films, which document day-to-day struggles of Palestinians under occupation and in exile. Now I’m feeling more guilty about that subscription, but they got many years out of me 😏

Actually I can say that the previously mentioned “adjustment” was legitimate, because I had watched slightly more Israeli films before the project began. Hence I could kind of bank those, while bingeing on Netflix. One other little “fix” that I’ve done to balance the numbers - I’ve also included some Iranian films.

Before anyone comments, I do know that Iranians are not Arabs. Arguably, however, Iran’s central involvement in the historical shenanigans of what was once the Near East, and is now the Middle East goes back a thousand more years than the Arabs’, and God knows they couldn’t be much more involved than they are right now, so it’s certainly legitimate to bring them into this discussion.

On the Israeli/Jewish side I’ve also thrown in some films which are not set at any point in the lands which are now so tragically disputed. In other words, these are not necessarily Israeli or Zionist-influenced films, but simply films which present the Jewish Diaspora experience, mostly of course in Europe, but also in America or indeed other parts of the Middle East.

I’m very sorry to say that several of these films will relate to the Holocaust (more commonly known in Israel, and among Jews in the Diaspora as the Sho’ah - השואה, which means “disaster/catastrophe”, without the religious sacrificial overtones of the word Holocaust). There’s no way around that, and no way to take the Holocaust out of the Middle East that we see now. Indeed, I am now coming to the view that future historians (assuming that humans survive this century with any memory of what happened) will look upon the European Sho’ah and the Palestinian Nakba - النكبة - without comparing - as a virtually contiguous event, just as they may look upon the First and Second World Wars as one big European and then World War, broken up by a fragile 21 year armistice.. I do appreciate that the latter statement might sound a little esoteric, and that the former is a statement which is prone to upset some people on both sides, but I can say that I personally am now finding it helpful to analyse what I now occasionally call the Sho’ah-Nakba as one chain of directly related catastrophic historical events.

There are in fact three discrete and distinct disasters here, but they come in such short succession, in little more than one decade between 1941 and 1951, that they do form what is effectively a direct chain reaction, even if direct causality is not easy, or even useful, to demonstrate. The first two are well known. The third less so, and therefore I’ll elaborate a bit.

- The Sho’ah - the near-elimination of European Jewry, 1941-45, leading to the last desperate immigration (Aliyah) to Palestine, 1945-48.

- The Nakba - the destruction of Arab culture and existence in Palestine, as a result of the 1948-49 War, leading to a wave of Palestinian refugees across the Arab World.

- The reflexive expulsion or exodus of Jews from their homes across the Arab and wider Muslim world, 1950-52 (and in subsequent waves over the next twenty/thirty years), including some communities, most notably the Iraqi Jews, which had a history in those locations stretching back longer than two millenia. There isn’t any recognised emotive word for this one, although some refer to it as the Jewish Nakba, or alternatively as the Jewish half of a so-called Double Nakba. Of course we have to note that this is language which could easily be deployed to deflect and diminish or even to dismiss Palestinian grief, so maybe we have to say that it’s not especially helpful. There is also an argument that not all of these people were expelled, that many chose to move to the Jewish State. Those are murky waters, probably.. What is clear, however is that the scope of the displacement certainly isn’t any smaller. We’re still talking about a movement of 900.000 people, and approximately 650.000 of them ended up in Israel.

Those who support the maximalist pro-Zionist-Israeli position dismiss the significance of Disaster #2. and at their most delusional they pretend that it never happened, or that Palestinians left their homes of their own accord. Or that there was no such thing as the Palestinian people, that they had all come from Syria or Egypt. “A Land without a people for a people without a land.” That is 🐮💩 of course, and actually there’s little more that I need to add. The case is closed. The next paragraph (or two, or three) will be much longer, and MUCH harder to write. I don’t mean to diminish Disaster #2 by writing so many more words on Disasters #1 & #3. It’s only that #2 is, in my opinion at least, a lot more simple to evaluate, and I feel that I’ve already said what was necessary on the morality of the case.

Now for the hard bit.

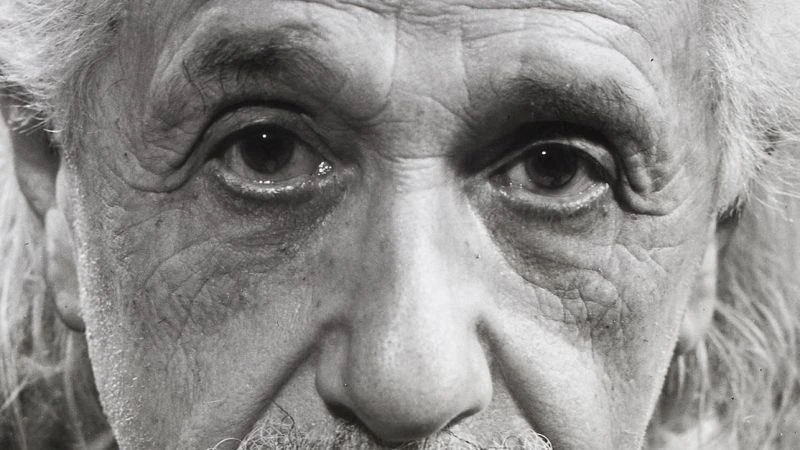

On the other side, it’s certainly much more complex, and that’s not any kind of a justification for anything. It’s just a fact. Let’s start by saying that there’s no logical argument that a very distant history in which you were the majority population in a territory two thousand years ago should convey the automatic right to return and take back control (shuddering Brexshit vibes) of that territory. However, if you know anything about Jewish history, you know that it’s not about logic. One way or another, the yearning to return (“next year in Jerusalem”) was an eternal thing, which bound together communities over generations in Germany, Spain, Iraq, Yemen…. all the way to India and possibly even China. Imposing cold 20th century logic onto the analysis of that is pointlessly anachronistic. Zionism from the very beginning (let’s say that it evolves fully formed from so-called proto-Zionism between 1860 and 1880) was always a strange hybrid and slightly schizophrenic creature. It simultaneously drew on the ancient yearning to return to Jerusalem, while calling for a Transvaluation of Values, a modernist secular rupture with the same religious tradition that had kept that candle burning for two thousand years. There are a million more things to say about that, but let’s try to keep this paragraph to manageable proportions. There were, and of course still are, Jews of all stripes who disapprove(d) of Zionism. Here’s a pretty revealing quote from a rather important Jew of the first half of the twentieth century. When asked to sign a petition condemning Palestinian Arab anti-Zionist riots in 1929, Sigmund Freud responded thus:

Dear Sir,

I cannot do as you wish. I am unable to overcome my aversion to burdening the public with my name, and even the present critical time does not seem to me to warrant it. Whoever wants to influence the masses must give them something rousing and inflammatory and my sober judgment of Zionism does not permit this. I certainly sympathize with its goals, am proud of our University in Jerusalem and am delighted with our settlement's prosperity. But, on the other hand, I do not think that Palestine could ever become a Jewish state, nor that the Christian and Islamic worlds would ever be prepared to have their holy places under Jewish care. It would have seemed more sensible to me to establish a Jewish homeland on a less historically-burdened land. But I know that such a rational viewpoint would never have gained the enthusiasm of the masses and the financial support of the wealthy. I concede with sorrow that the baseless fanaticism of our people is in part to be blamed for the awakening of Arab distrust. I can raise no sympathy at all for the misdirected piety which transforms a piece of a Herodian wall into a national relic, thereby offending the feelings of the natives.

Now judge for yourself whether I, with such a critical point of view, am the right person to come forward as the solace of a people deluded by unjustified hope.

Of course Freud died only a few weeks after the outbreak of World War Two, and we can’t know whether his view might have changed in the light (or more properly the darkness) of the Holocaust. Who knows? Let’s assume that his mind was made up, come what may. To come back to the present day, there’s very little else which would bring a secular leftist anti-Zionist Jew together with a member of the Satmar sect - but they do share the conviction (albeit for VERY different reasons) that the State of Israel has no moral right to exist, and that however desperate the imperative of fleeing from and preventing the repetition of Disaster #1, it still doesn’t provide the justification for what happened in 1948, and what continues to this day. One common anti-Zionist argument is that the Jews of Europe could or should have been offered a territory at the end of World War Two, most likely at the expense of Germany, just as Poland was awarded a large swathe of German territory in the East (to compensate for the territory that Uncle Joe took from its East). I am even quite sure that I am not hallucinating about having read recently that there was a moment, some time between 1945 and 1948, when the idea of a Jewish state in the Rhineland was floated to David Ben Gurion, and that he did briefly consider it as a genuine option. Very frustratingly, I have searched for more on that ever since, and failed to find any discussion of it. I couldn’t even find the orginal article which I read. I’m pretty sure that I didn’t imagine it, however, and I have not given up, so I will amend this paragraph as soon as I find more information on that. But anyway, let’s assume for a moment, if only as a pure hypothetical, that the proposition was put to Ben Gurion, and that he did take it seriously. There’s a very difficult question which follows immediately from that - would it have been possible, let’s say in 1947, for any Jewish leader to persuade any Jewish people that a state bordering Germany was a viable, let alone an attractive proposition? Would you want to live in a house next to the people who murdered your entire family? And more generally, if you were a Jew in Europe in 1947, looking at the Iron Curtain coming down, with the fear of another war imminently starting up again, would you really feel safe *anywhere *on that continent? Denmark, maybe? They had a good war on that score, but not too many others did. And so…. even though I have THE GREATEST respect for Jews who refuse the Zionist orthodoxy on the obvious moral principle that it is (it was, and still is) manifestly unjust to expel people from their homes in order to establish a Jewish homeland, I also cannot find it in myself, as a European with my own small inherited part in the history of it all, to condemn the instinct to flee this continent. Of course we might say that they could all have gone to America. Many did, of course, and we may argue that it was a better choice. But even then, they couldn’t ALL go to America either. So……… ????????? What’s the answer, Genius? Answer - there’s no answer. The answer is what we’ve got, Dude, and the only thing we can do is to work it out from here. All this is by way of saying - don’t diminish the importance of Disaster #1. This whole thing probably wouldn’t have happened without that. We know what line is coming next, don’t we?

Two wrongs don't make a right.

Correct. We’ve got two wrongs, right up next to each other. Neither of them is going away. The only way is to figure it out from here, the good way, and not the Hamas-Netanyahu way. One of the most brutal presentations of the issue that I’ve seen so far in the movies that I’ve watched comes in the Amos Gitai film Free Zone. It is honestly not a good film at all, despite the fact that it’s got some pretty heavy-hitting Israeli and Palestinian actors. I’ll be a bit more blunt - it’s an inexplicable formless mess of disconnected scenes which don’t consitute anything which I can call a story, but it does have one good scene, where a Palestinian woman (played by the ubiquitous Hiam Abbass) is interrogating the Israeli character, in Arabic, about where she comes from. The Israeli (played by Hanna Laszlo) replies in Hebrew, even though she understands the Arabic perfectly well, that she comes from XYZ, whatever the name of the place was (I’m not going to watch it again to find out!!!) and then the Palestinian continues the questioning - And where did your parents come from? “Israel.” And your grandparents? “Auschwitz.” Full stop. End of conversation. And that’s it. More or less the only interesting scene in that film. You don’t need to watch it now. I’m no fan of using the Holocaust to justify everything that’s going on right now, or to explain away all the other terrible things that have happened in these last decades. I can’t. I don’t want to. I won’t! But I also can’t deny the power of that dialogue, so beautifully acted by those two ladies, who managed to fish one good thing out of a film which was otherwise so painful to watch (for the wrong reasons).

As for Disaster #3, this is the invisible elephant in the room, and it will be the subject of several posts in this series. One of them is already in the bag at the time of writing this introduction. ⇒ Find it here ⇐ The essential problem here is that it’s easy enough to understand the anger of Arab populations after 1948 at “the Jews” and that there would be paranoia about the Jews in their midst becoming a fifth column for Israel. Of course some of those Jews were enthusiastic about the idea of a Jewish state, but most assuredly they were a minority to begin with, and most Middle Eastern Jews certainly had no strong urge to move from the lives that they had lived for generations, and even millenia, in those lands. And so when they were forced to leave (those who did leave against their will, at least) why should we assume that they wouldn’t feel exactly the same rage that the Palestinian Arabs felt? In their case, they could justifiably feel angry at the Arabs who expelled them, AND resentment against the European Jews who first caused them to be expelled and then treated them as second class citizens when they came to Israel. That’s some seriously complicated 💩💩💩 there, which is a very long way from working itself out, and it doesn’t help very much that there’s virtually no acknowledgement or discussion in the public discourse of this very seriously important aspect of the whole historical problem. Is there a right of return for Iraqi Jews to the lands where their ancestors spent more than two thousand years? As long as we can say that they were forced to leave, I think so, yes, just as much as for the Palestinians. One true thing is that these people didn’t become stateless in the way that Palestinians did. That’s true, but there was still an emotional wrench and an enormous economic loss. What about the BUT THEY STARTED IT! argument? The Iraqi Jews didn’t start it. They were more or less happy where they were for two thousand years, give or take the odd occasional Mongol/Tatar rampaging horde. Would that return be any less difficult to arrange than the return of every single 1948 Palestinian refugee to their rightful properties? Obviously not. It would be incredibly difficult, and it’s of course unimaginiable if we look at today’s Iraq, for God’s sake. But I honestly believe that it’s only when that discussion is opened up, in full, that we’ll start to figure this thing out. It might take a while yet.

I do not wish to reduce the history only to these three core disasters. Many significant events have of course complicated the situation since the creation of millions of refugees between 1948 and 1952 - in 1956, 1967, 1973, 1982, 1987, 2000, 2023…… and we also need to go back before 1948, 1941, 1936 or 1933. The sadly duplicitous historicalinvolvement of my own country in collaborative rivalry with France is rather important to analyse here. There is plenty of literature - fiction and nonfiction - on the subject, but a rather disappointing amount on film. There are lots of British films and series about colonialism in Africa and India (including a whole Raj Rage in the 1980s!), and a similar quantity of French material on North and Subsaharan Africa; but only one of the films that I have so far seen, Theeb, contains even an oblique reference to the carving up of territory after WW1. That is the functional starting point of this mess that we’re looking at 100+ years later; although of course we CAN continue to go back recursively, to 1903-06, 1894, 1881-1882, 1491, 1492 (not Columbus!), 1099, 1096, 634-638, 70 CE……. keep going ….. to the Big Bang or the Garden of Eden, wherever you prefer.

Let me be very clear - about the three aforementioned disasters. I have no intention either of comparing one disaster with another, nor of diminishing the significance of any of these terrible events to the affected peoples, and certainly not of using one disaster to justify another. Explaining is not justifying. Each disaster had its own unique character, but the marks of all three are evident right up to the present (albeit the third disaster is rarely discussed, little understood and barely acknowledged on the protesting left, which is a BIG problem). After many years of thinking about this conflict I do believe that the only way for these two diverse peoples to reconcile with each other is to acknowledge each other’s pain and to choose to accept each other as respect-ful and respect-able neighbours. I waited almost a week before first publishing this post, because I was thinking so much about the language (and am still tweaking it several weeks later). In the end, I cut out a whole load of stuff that I decided was sounding more like a rant than a composition. Never mind. I suppose I’ll be returning to the subject anyway.

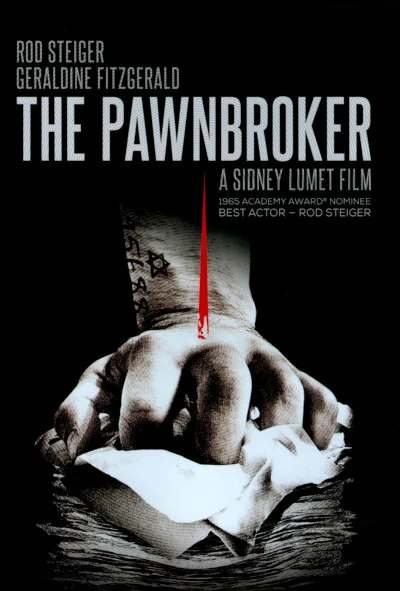

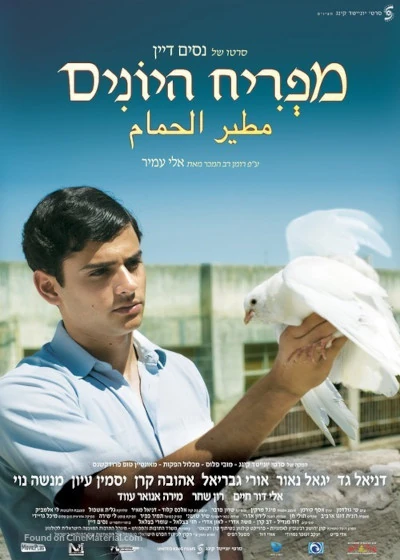

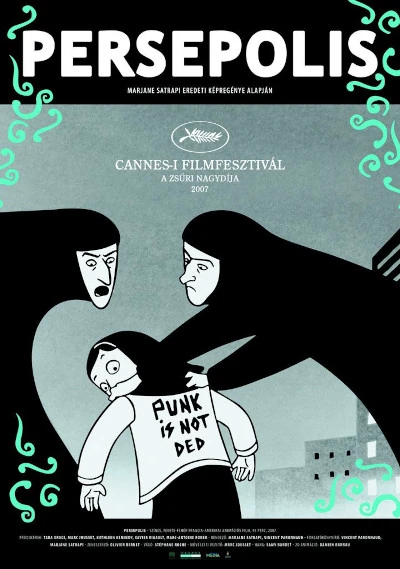

The last twenty or thirty years have seen the evolution of a certain genre in cinema which presents the Holocaust within some kind of standard template. I’m thinking of The Pianist, Schindler’s List, La Vita È Bella, and (most egregiously inadequate for me) The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas. I find that they all have shared tropes, and while all of them (apart from the last, honestly!!!) are undoubtedly worthy and sincere works, each of those films falls short of the mark, for me, in different ways which I need to think about a bit more. The gravity of the subject makes it hard to get it right, very obviously, and so I only choose the films which I find to have hit the correct discordant notes. Three of those films you see below. The others will reflect the richness and diversity of Jewish experience across the historical diaspora. One of the films in the pics below, which is sometimes marketed in English as Farewell Baghdad, but is known to IMDB as The Dove Flyer, relates to Disaster #3, and it is supposedly the only film to date in which the dialogue is in Judeo-Arabic.

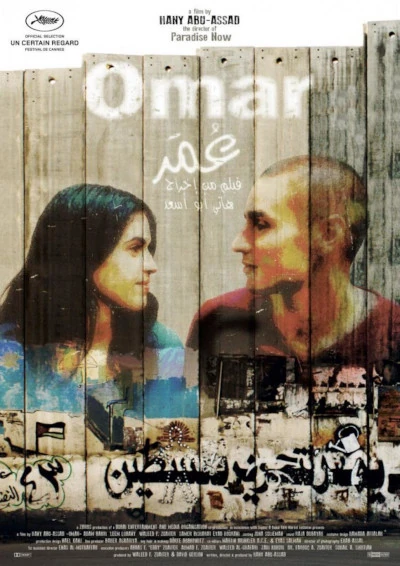

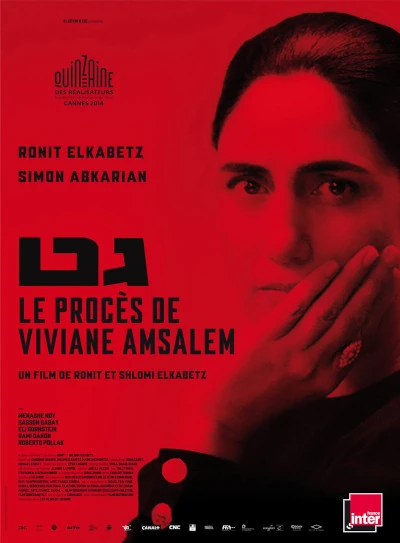

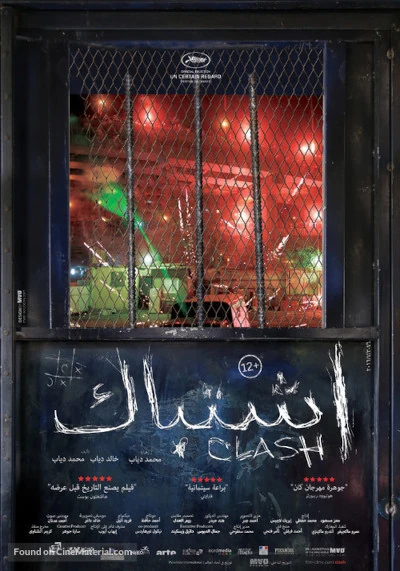

At the time of writing these words I have watched approximately fifty out of 130+ films that I’ve racked up on the two lists. Part of me feels that it would be better to wait until I have watched and absorbed everything before writing, but of course like that I might end up waiting at least half a year, as other projects assert themselves. So let’s begin! I’m going to try to group films in some kind of thematic arrangement as much as I can, but the only way to do that perfectly would be after watching everything, and we’ve just established that I’m not going to wait. I’m going to try to avoid giving too many *spoilers *about the films that I discuss, and if there are spoilers I’ll give prior warning that they’re coming. My goal is also not to review these films - there are people who are qualified to do that, and I’m not one of those people. Apart from a few strategically chosen exceptions, most of the films are works which I have liked or even loved, and to which I would give a score of 8/10, minimum. So unless stated otherwise (as above!), assume that I liked the film. I’m going to react to films, sometimes on their own and sometimes in direct comparison with a film from the other side, and talk about each film in the context of my (not toooooo negligible) understanding of European and Middle Eastern history.

(Much later edit) Just a few site navigation pointers. After first starting this blog on Blogspot/Blogger, I moved away from there once I realised the ambition that I was leaning into, and the limitations of that platform. And so basically I’ve built the whole thing myself, with all the trimmings that I wanted to create, partly to feed my inner geek but mostly to do justice to the subject. There are, therefore, two pages on which I list films from both “sides” (AS IF there are only two sides!!!!) Each page is grouped into topical or geographical categories. I don’t want to place one side higher or lower on the list than the other, but because Israeli comes before Palestinian in the alphabet, you will find that the section of Israeli and Jewish films is placed higher on the preview pages, here and here. I could randomise that somehow, but hopefully readers will appreciate that a lot of work has already gone into building this site, and any more such tweaks would be pointless overkill. When you hit on those catalogue pages you will find that films which I have already specifically written about are linked to from those pages. Wherever I could find them, I’ve also added YouTube links to trailers, or even to the full movie if available on YouTube (hopefully not in contravention of any copyright - I’m assuming that YouTube have that stuff under control). I also have pages for prominent actors and directors. The actors are happily balanced pretty much 50/50 male-female, but of course things aren’t so far advanced on the directorial side, and it’s still heavily weighted towards the male column. There’s also a page here for what are essentially now chapters of a book (albeit a book that still needs a lot of editing at the time of writing). I will periodically change the look of the site. Any friendly and constructive suggestions are warmly welcomed.

Final words of warning - many of the films here are just as brutal and harrowing as you might easily imagine, so much of this is not for the faint-hearted. Furthermore, if you’re some kind of an originalist who doesn’t believe in graven images, then I can only hope (and indeed pray📿🙏) that you will find other people to torment with the post-modern medieval bile that is in fact a travesty of the good name of the misunderstood Middle Ages.