واجب

Wajib (2017)

This week I need to write about something that is at least bearable, It’s late January, the sky has been slate grey, and the blues hit me two weeks after Blue Monday. I’m going to be writing about some pretty depressing and brutal stuff in weeks to come, and I’m just not sure that I’ve got the mental and emotional strength for that this week. So here I’m going to write about a film which is gentle and wistful, occasionally funny, and occasionally sad and touching. The beauty of this film lies in the fact that - despite not containing one single word of dialogue between either of the two protagonists and an Israeli character - there are more than enough references, oblique and acute, to reveal what it’s like to live day to day as an Arab citizen in the Jewish State.

Wait. I said “Israeli”. But the characters in this film are in fact themselves Israeli. Israeli Arabs. Israeli Palestinians. Citizens of Israel, but not citizens who are obliged or indeed even invited to participate in the military service which stereotypically constitutes the Jewish State’s central rite of passage. Like every other Arab born within the 1948 borders, these two Arab men live with the feeling of daily alienation that comes of being a marginalised and (certainly when Israel tacks as far to the right as it is at the moment) a scarcely tolerated community. There’s a weird reciprocity between the unease that Israeli Arabs feel in their daily lives, with the fact that their very existence as a community serves as an uncomfortable daily reminder to the Jewish members of the Jewish State of the surrounding Arab populations. I suppose that the reason for pairing and contrasting this film with Zero Motivation, a film about women serving in the Israeli army, is that the two films share themes of superfluous existence, confinement, and a sense of the absurd in their daily lives. I would say that Zero Motivation veers much more towards the bitter and spiky end of the bitter-sweet spectrum, but I can leave that for the viewer to discover without my spoilers.

It is possible that some readers are in need here of a brief historical explanation of who the people in this film are. I’ve never studied in any great detail the 1948 War known to the Israelis of course as the War of Independence (Milknemet ha’atsma’ut - מלחמת העצמאות), and to the Palestinians as the Nakba (the Disaster - النَّكْبَة) - so I’m certainly not in any position to give a blow-by-blow account of how the majority of Palestinian Arabs ended up having to flee their homes to Gaza, the West Bank, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and beyond… and why the people in this film, for example, were able to stay in their homes. It’s a subject which I intend to study a little more closely, mainly by reading more about it, but also by watching films such as Farha and Tantura (the first of those I’ve already seen at the time of writing, and the second one is on the list).

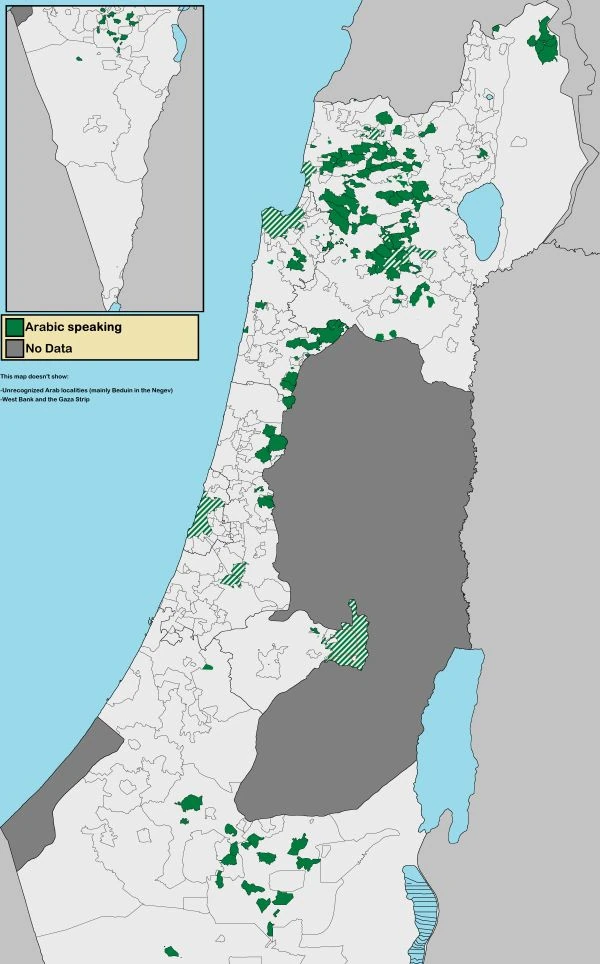

The simplest explanation that I can give is that there were some areas of the country where the Arab populations were not in a position to flee the fighting, or where they felt sufficiently reassured that they would be safe to remain in their towns and villages. I don’t have the learning to say which of these two feelings was the stronger in most cases, but in any case the outcome was that once fighting ended in the summer of 1949, roughly 20% of the pre-war Arab population remained on the Israeli side of the line. This map gives a rough idea of where these Arabic-speaking areas remaining within the 1948 borders are. Notice of course that the area around Tel Aviv was cleared pretty much entirely of Arab towns and villages, apart from some parts of the old port in Jaffa. The estimate is that approximately 400-500 such places were essentially erased from the map.

Those Arab communities which remained within the borders, and which had not allied themselves with the Israeli side in the war (alluding there to the historic allignment of the Druze and some Bedouin) were subsequently placed under direct military rule until 1966, soon after which the Arab populations in Gaza and the West Bank found themselves under the direct military rule which has continued through to the present day, at least as far as the West Bank is concerned. Gaza is a slightly different story. Not a pretty story, obviously.

Let’s zoom in on Wajib. The setting of the film is Nazareth, which I think should be a familiar name to anyone who’s ever heard of a chap called Jesus. One personal reaction while watching was that I cursed myself several times for the fact that I never visited Nazareth during the year that I studied in Jerusalem. I know that part of the reason was that Israelis talked of Nazareth as a hotbed of Arab political activity, and would warn people off from visiting. Of course I now look back and find it quite ridiculous that I, the blondest of Europeans, paid serious heed to this advice, but I was young and a long way from the finished article.

The scenario of the film is pretty simple; Abu Shadi and his son, also called Shadi, are driving around the city all day to hand out invitations to Abu Shadi’s daughter’s wedding. There is tension between them over several matters, including the fact that Shadi Jr. has decided to move permanently to live in Italy, about Abu Shadi’s oppressive expectations of his son, about the fact that he doesn’t think being an architect is good enough, and the fact that his girlfriend in Italy is connected to PLO activism and therefore problematic should Shadi Jr.. wish to return home with her. There is also Junior’s defence of his mother, who now lives in the USA with her second husband, and a big argument over whether to invite Abu Shadi’s Jewish Israeli friend to the wedding (watch the film to understand why I’ve italicised “friend”). Little nuggets of gossip are dropped at every meeting, and there’s a story with a dog (whose symbolism I would be eager to discuss in the comments), but of course it would be a massive spoiler for me to talk in detail about everything that happens in the course of the movie. In any case I would have to watch it again to remember all of those nuggets. In a way, I suppose that I needn’t worry too much, as there are no massive spoilers for this film. Just watch a father and son who haven’t seen each other for a while, getting to know each other again. I certainly will watch this film again, but there’s a long list of films to get through. amd many of them feature the actor who plays Shadi Jr (more on him below, and in future posts!)

There’s one further thing to be aware of here, and which I’ll need to hold in my mind when I closely watch the film a second time - Abu Shadi and Son, and the whole community around them, are Christian Arabs (Nazareth - Christians - makes sense, right? - in fact, the Hebrew and Arabic words for Christian - Notzri נוצרי and Nasrani نصراني - just mean “someone from Nazareth”). Wikipedia informs me that Christians comprise approximately ten percent of the Arab population between the River and the Sea. Contrast with Lebanon and even Syria, where the Christian population is substantially higher than that, and we see that these guys are a minority within the minority (which in turn represents an overwhelming regional majority, always psychologically menacing to the Jewish population, as previously stated). Without getting too *meta *and academic about that, we can easily speculate that this Christian Arab identity is a particularly complex and more to the point a fragile one to sustain within all the entanglements and constraints imposed by the politics around them. This is no doubt why Abu Shadi is vexed by his son’s flirtation abroad with radical nationalism - he sees in that a threat to, or maybe better to say a disregard of his own careful efforts to preserve the local Christian Arab identity within the Jewish State.

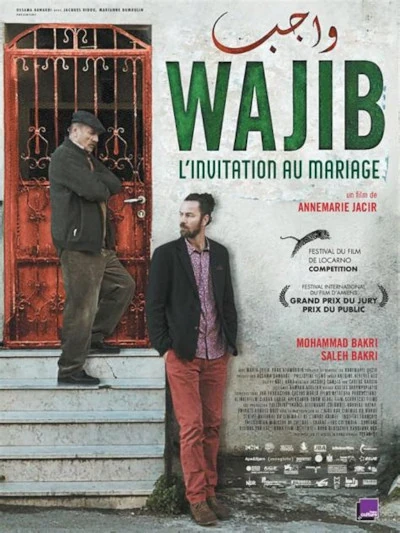

As the reader can perhaps perceive, I haven’t quite finished with this film. I watched it fairly early on in the process of this project, and I’m definitely feeling like I’ll need to go back and watch it again quite soon. But of course there are quite a lot of films to get through, and so that will have to wait a while. Just a few notes about the production. The director of the film is Annemarie Jacir, who directed several other films on the list, starting with Like Twenty Impossibles (still trying to figure out what that curious title is all about). The other REALLY CUTE thing is that the actors playing the father and son in the film are themselves father and son. Mohammad Bakri and Saleh Bakri. Presumably the two men brought some of their own personal tensions to the roles, and that makes their acting out of the relationship quite enthralling. Saleh is going to turn up at some point in several more films that I’ll be talking about here, including The Band’s Visit, The Present, Bonboné and Costa Brava, Lebanon. There’s no fancy coda for this post. Watch this film - it’s cute, touching and funny. And the Middle East needs a bit more of that stuff.

After writing this post last week, I was hit by a wave of nostalgia, so it turns out that we do have a coda. Regarding what I said about not having visited Nazareth., I need to be fair to myself. It’s not that I was so blinkered or narrow-minded that I didn’t come into contact with any Arabs during my time there. It was more about shyness and nervousness than any kind of conscious avoidance. After all, I did try to study a fair bit of Arabic while I was there, and one of my fondest memories of that year is of my two (no, I think it was three!) visits to Umm al-Ghanam, a small town (or large village?) near Afula. The people there were so inviting, so lovely, and I feel very guilty now that I didn’t keep in touch with them. Hopefully I can somehow get back in touch with the help of what I’m doing here. I’m putting a couple of pictures here, hoping to jog someone’s memory!