كستا برافا، لبنان

Costa Brava, Lebanon (2021)

I don’t know who I heard this from, or even whether I heard it at all from someone’s mouth, but the saying goes that all roads to understanding the Middle East pass through Lebanon. It’s just a throwaway cliché, but there’s probably a lot in it. For me personally, my own interest in and awareness of the Middle East started in two places: Iran and Lebanon, not Israel/Palestine, and so it’s perhaps quite a strange quirk that I ended up studying Hebrew rather than Arabic and/or Persian. My first memory of a major world event was the Iranian Revolution in 1978-79, shortly followed by the Iran-Iraq War (then known as the Gulf War, but subsequently stripped of that title). I don’t remember hearing too much about Israel until the full-scale invasion of Lebanon in 1982. In the subsequent years, following the Israeli withdrawal from Beirut, and the bombing which led to the withdrawal of the Multinational Force in 1984, came the daily drama of the British hostages, Brian Keenan, John McCarthy Terry Waite and many other Westerners. Each of those three eventually got out of there, along with the majority of Americans, Germans, French and so on. The hostages that we never talked about were the hundreds of Lebanese and Palestinians, from all sides of the Civil War, many (most?) of whom never came back home, assuming that there was even a home to return to.

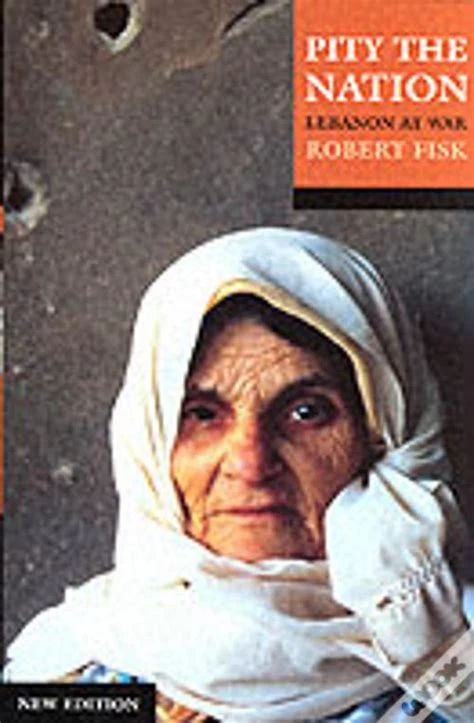

Younger readers won’t remember the 1975-1990 Lebanese Civil War, but it was pretty much a defining world conflict for anyone with a developing political consciousness who was coming of age in the 1980s. That’s me, then. I was aware of how complicated Lebanon was several years before I understood that the situation immediately to the south of it was equally complicated, and that it was the earlier conflict in precisely that place which had so generously contributed to Lebanon’s problems - problems which would have existed anyway but which were certainly turbocharged by the addition of a Palestinian refugee population, many of whom fell victim to one of the most iconic brutal events of the Civil War. While I was studying for my unfinished PhD, I had a phase in which I got obsessed with the Lebanese Civil War, and so instead of ploughing through Hebrew texts from the late nineteenth century, I was reading the memoirs of the hostages mentioned above (there were some personal reasons involved in that!). Most salient of all in my memory, however, was my reading of the classic work of long-form journalism which you see in the picture above (tap or click on it to find out more). I very clearly remember walking past Salisbury Crags, reading that book along the way because I was so obsessed. Who does that any more?!? I saw again names like Michel Aoun (President of Lebanon until only recently!); Nabih Berri (who is quite unbelievably at the time of writing still the Speaker of the Lebanese Parliament, and making Joe Biden look like a teenager) and Walid Jumblatt (the trusted party that Terry Waite was last seen with before he disappeared for five years). Still going strong, dear old Walid, albeit now apparently retired to his dacha - no doubt the young ones still visit him to kiss the ring. Even though the men bearing them are still alive and kind of active (in the sense that Mitch McConnell is still active), these names are already little more than footnotes in history for Millenials and Gen Z. However, they are names that were regularly mentioned on the news during my adolescence, along with the name Gemayel (using the French spelling), which will certainly come up again in the next posts.

Made in 2021, Costa Brava, Lebanon is set in “a near future”. When exactly that is supposed to be is unclear, but let’s assume that it’s approximately now. I may have missed it, but I don’t recall any overt mention of the Lebanese Civil War in the film, which means that younger viewers could conceivably watch it without once being aware of the war’s significance here, other than perhaps wondering about the historical background to the anti-corruption protests which are shown to be taking place in Beirut. Part of the reason for the lack of overt mention is that the memory of the Civil War was far too painful for all concerned, and there was an implicit agreement among all the communities not to talk about it, and to try to get back to living a normal life. But what exactly is a normal life supposed to look like after fifteen years of tearing each other apart, and how are you supposed to stop it happening again if you don’t look at it properly? My understanding, without having studied it too closely, is that the Civil War ended not with any kind of [Truth and Reconciliation Commission](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ Truth_and_Reconciliation_Commission), but with the rival militias agreeing a power-sharing deal, under the stern gaze of Hafez al-Assad’s Syrian government. In more cynical terms (God forgive me), militia leaders turned into mafia dons and carved the country up between them. The deal wasn’t actually all that different in formulation from the arrangement before the Civil War started (a Maronite Christian president, a Sunni PM and a Shi’a Parliamentary Speaker - it’s called consociationalism, apparently), so we may indeed wonder what the hell the fighting was all about. This is not to say that there hasn’t been anyone in the years since 1990 who didn’t try to move things on a bit. Rafic Hariri was one such individual. Look what happened to him.

The family in this film (Walid, Soraya, their two daughters, and Walid’s mother) appear to have moved out to the hills overlooking Beirut in order to get away from the stress of living in a city sitting on a powderkeg, and from what we see in the first minutes this appears to have been a very sound decision. They are living the Good Life (sorry, that’s a British Baby Boomer / Gen X reference). The children are happy and healthy. They have their free range chickens, their orchards, and a beautiful view over the valley. Everything is swell.

And then one day they learn that the land in the valley below them has been sold off by Walid’s sister (without telling him, great!), and that it is going to be used for dumping garbage from Beirut. There are a few kalaam faadi (“empty words” - كلام فاضي) about ecology and sustainability, but Walid and Soraya understand from the start that they are up against a system which will pay no heed to their protests. Still they decide to stay and fight anyway. The rest of the film is about how they face the challenge, and what this does to the family. The leitmotif of the film is the habit of Reem, the younger daughter, of counting to 44 every time she sees or senses trouble. It’s simultaneously delightful and disconcerting, and a superlative dramatic device. For the older daughter, Tala, who is coming of age, these events come at a very sensitive moment, but okay….. no spoilers. I’ll only ask that if there’s anyone who reads this and has some idea of whether 44 is a number with a particular significance, please let me know in a comment. 👍 شكراً جزيلاً 🙏

In my imperfect and not-guaranteed-to-be-forever-precise 50/50 Arab-Israeli-Arab-Israeli-Arab-Israeli system this film is twinned with Broken Wings. Click or tap on that link to see the post, in which I’ve already detailed the reasons for pairing them up. I’ll just repeat them in summary here, however. Both films are stories of normal families being blown apart by an external event, and both of them include an accomplished musician in the story, one of them established and apparently retired from the business, the other one just starting out in the face of many difficulties. The stories are also separated by a geographical distance of little more than a hundred miles, but unfortunately due to the politics of the Middle East they are also worlds apart. Ironically, though, the part of Walid is played by an actor who has worked on both sides of that troubled border. I was only mentioning his name this time last week, and will be mentioning it again soon, as Saleh Bakri is almost certainly going to top the charts for most mentions of an actor in these posts. The only possible competitor is Hiam Abbas, who hasn’t turned up in any post yet, but will be there soon enough. Having commented in the post about Broken Wings that the Israeli films which I’ve seen so far point to a pretty small thespian world, the circle of Palestinian actors seems to be even tighter. Nadine Labaki, who plays Soraya, is also going to turn up in a post next week (or whenever I get around to writing it) as she appears in more than one of the Lebanese films which I haven’t seen yet, at least one of which is likely intended for inclusion in that post.

The next posts are going to be hard. Much talk of war. Better get used to it…. So if y’all don’t mind, I’ll put the pen (that is to say, the keyboard) down now.

👐 تصبحو على خير احلاما سعيدة 🙏