ימים נוראים

Incitement (2019)

As I’ve already explained elsewhere, for the week and a bit leading up to Purim I’ve been watching only Iranian films. Read that post for more on the external associations of Purim. Anyone who’s read the Book of Esther knows the story from ancient Iran of the foiling by Esther and Mordecai of the plot against the Jews by the scheming Haman. Here I’m focusing on the Jewish internal dynamics. I think that it’s safe to say that Purim is not a Jewish holiday that most non-Jews are especially aware of. Of course it’s not as well known as Passover or Rosh Hashanah and the other holidays that come in the Jewish New Year; but it’s also definitely not the most obscure. From the time that I stayed in Jerusalem I’ll give that honour to Lag baOmer, which I had never heard of before, and never read too much about since. All that I remember about Lag baOmer is that they light bonfires, and I really can’t remember why (I’ll brush up on Wikipedia). The strongest association now is of a Danish friend, who had a BIT of a drinking problem, getting particularly loaded that night and probably coming perilously close to ending up on top of the particular bonfire that we were hanging out around. I’m only half-joking. I felt really bad for him that night. I hope that he’s still around, and that one day he might read these words.

Despite the fact that I had already studied deeply around the subject of Judaism for a couple of years, it was only in Jerusalem, in 1994 (shudder) that I found out what Purim was. What is perhaps most interesting about Purim is that it’s a holiday that marks an event in the Bible not especially marked out by miracles or a guiding divine providence in the way that the holidays deriving from the books of Moses are. Purim is much more earthly and human. Esther and Mordecai get the better of Haman by being smarter than him. God may implicitly be smiling upon them in the story, but there’s no burning bush or parting of waters. Bear in mind that Esther is certainly one of the last (if not the very last, setting aside the Apocrypha) of the books canonised in the Hebrew Bible. Symbolically, then, we can say that the book marks the transition from the age of myths and legends, for which we often have negligeable historical evidence, into a historical age where we can begin more thoroughly to cross-reference the Jewish account with what we find elsewhere.

I suppose that it’s also not unsymbolic in a way, having orignated in Zoroastrian Iran, that the Purim story contains within it two profoundly contrasting strains: there’s a bit of Ahura Mazda, on the side of the light, up against the darkness of Angra Mainyu. On the positive side of the ledger there’s the exchange of gifts, of the kids’ fancy dress, and of the Hamantashen (sweet pastries in triangular shapes, maybe to resemble the shape of Haman’s hat). That’s all sweet and lovely (and thanks very much, BZT, for the evidence, right, of the cute side of Purim). On the dark side, you have a couple of things that I recognise well enough from my own culture - there’s a commandment to drink to excess, in commemoration of the fact that there was a massive drinking festival going on at the Shah’s court at the time of all these events, and there’s also a tradition of burning effigies of Haman, just as the English still do with Guy Fawkes on November 5th. Since there’s really nothing about Guy Fawkes Night that I find especially edifying, I’ll say that the burning of effigies is not something that I find attractive in any culture.

Purim falls on the 14th day of the Jewish month of Adar (or the 15th in Jerusalem, for obscure reasons that I won’t go into here). This corresponds to late February or March on the Western calendar. I’m not going to go back and check, but I remember it falling in late February in the year that I stayed in Jerusalem. There was a big fancy dress party, at which I didn’t get as drunk as commanded by the rabbis, and then the day after was seemingly a fairly quiet one until my friend from down the corridor came to ask me if I’d heard the news about what had happened in Hebron.

And……. I’ve just gone back and checked 😐 In 1994 Purim fell on February 25th, and just like this year, as it happens 😬, it was overlapping with Ramadan. Shortly after 5:00 am, Baruch Goldstein entered the building of the Cave of the Patriarchs, a site holy for both Muslims and Jews. There were supposed to be nine Israeli soldiers on duty, but four of them were late and there was no officer present. Wearing his army uniform, Goldstein passed the guards unchallenged. He was carrying an assault rifle and a total of 140 rounds of ammunition, but they assumed that he was an officer who was going to pray in one of the chambers reserved for Jews. He then passed through the Hall of Abraham and entered the Hall of Isaac, where approximately 800 Palestinians were conducting their morning prayers. Accounts of such events will of course always differ, but survivors reported that he waited until the woshippers performed the act of sujud, prostrating themselves on the floor. He then threw a grenade into their midst and opened fire. 29 Palestinians were killed, and 125 were wounded. Goldstein himself was eventually overpowered by the crowd, and beaten to death. Eyewitness accounts seem to be far too confused to determine whether or not Goldstein had acted alone. Read the Wikipedia article or [this article](https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/ hebron-massacre-hell-comes-to-a-holy-place-did-baruch-goldstein-act-alone-eyewitnesses-afterwards-spoke-of-seeing-another-man-also-dressed-as-a-soldier-handing-him-ammunition-1396679.html) written in the immediate aftermath. What you decide may be determined by what you already think. That’s just how we all are, I suppose.

This event was certainly one of the most awful and dolorous in the long cycle of violent revenge in this conflict, and one of the most iconic - apologies if it seems distasteful even to use that particular adjective, but I’ll try at least to explain why it’s an apt one. Alas, the event was hardly unique, and indeed Israelis and Jews from all ends of the left-right peace-war spectrum may well be quick to point to an equally iconic massacrein Hebron in 1929, in which 67 Jews and 9 Arabs were killed. This was part of the Palestine Riots of 1929, which were certainly a major escalatory event in the Arab-Zionist conflict. Although it was not until 1936 that the full scale Arab Revolt broke out, leading the government of the British Mandate to dramatically limit Jewish immigration, 1929 is considered to be the year that the simmering tensions of the first decade of the Mandate broke out into open-ended communal violence. Read all about it and decide for yourself WHO STARTED IT. Once again, I suppose that your decision may well depend on which side you lean towards. I’m trying very hard to stay neutral. Not much love is coming to me for that, I know!

What is especially ghoulish and disturbing about the Goldstein attack is that there’s something Janus-faced about it. What I mean by that is that it faces both back into the past to provide the justification of historical revenge, but that there was also something consciously *preemptive *about it. And now we’re back to talking about Purim. The story goes that Esther and Mordecai foiled Haman’s plot by preempting him. No-one can know exactly what was going through Goldstein’s mind (and would you want to?), but bear in mind that this attack occurred not even half a year after the famous Rabin-Arafat handshake on the White House lawn, marking the official beginning of the Oslo peace process. It’s almost trivial to imagine that an extremist like Goldstein would see Arafat as a modern-day Haman who must be thwarted before carrying out his plot to destroy the Jewish people. And so he did what he did. Of course he was condemned by Rabin and anyone in the peace camp; and Kach, the extremist political party that Goldstein belonged to, was finally banned outright (having previously been barred from standing in the 1992 election). However, there was a disturbing general silence on the right, and on the extreme right Goldstein became an instant popup martyr, declared by one settlement rabbi to be “holier than all the martyrs of the Holocaust”.

Incitement is a meticulously researched attempt to reconstruct the movements and actions of Yigal Amir in the two years between that Rabin-Arafat handshake and Amir’s assassination of Rabin in November 1995. I just told you the ending, if you didn’t know already. No need to worry about giving away any spoilers with this one. The only spoiler would be to describe every moment in the carefully described buildup to the moment when Amir steps up and fires two bullets into Rabin’s back. I’ll just describe three scenes from the first fifteen/twenty minutes, elaborating a little where it feels appropriate, and those who are sufficiently interested will go and search the film out.

The film begins with the sound of Rabin’s speech on the White House lawn. We see Amir listening to it on his radio while doing his part-time job cleaning up in a cemetary. The speech continues playing as he drives from his job to his campus at Bar Ilan University< (which was known at the time for being home to a disproportionate number of right wing religious students). On the way Amir stops to join in a right wing anti-Oslo demonstration which is holding up the traffic, and Amir shows evidence of his cunning by avoiding arrest at the demo with some sweet words to a policeman. Having arrived at the campus, we see him at a political meeting, in which we hear Benny Elon, a rabbi and later (from 1996🤮) a Knesset member for Moledet, which was a far right competitor/successor party to Kach. While in the foreground Amir asks his classmate for a peculiar favour, in the background we hear Elon speaking about the aforementioned 67 Jews killed in Hebron in 1929. He goes on to outline the principles of religious Zionism, derived from the writings of Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook, the first Chief Rabbi of Palestine under the British Mandate. There were actually two Kooks, father and son. It’s the son, Zvi Yehuda Kook, who developed the more complex thought of his father into the rough-hewn and brutal fundamentalist ideology which today directs religious Zionism in the hands of Itamar Ben Gvir and Bezalel Smotrich.

If you’re on the pro-Palestinian and anti-Zionist side, obviously I appreciate that you don’t like any flavour of Zionism, but nonetheless I’m going to tell you for your education that the ideology of fundamentalist religious Zionism needs to be contrasted with the two previously dominant versions of Zionism which had competed with each other up until the 1980s: Labour Zionism and Revisionist Zionism. One of the three (sadly now the weakest of the three) you can work with, and the other two you probably can’t. Labour Zionism and Revisionist Zionism are both secular in outlook, but differ left-right on economics, and of course on territorial maximalism. The oringinal Revisionist vision of the Jewish state envisaged territory on *both * sides of the Jordan, but I suppose that most of them at least gave up on that eventually. After thirty years of Labour Zionist dominance, in the 1970s the Revisionists, led from 1948 by Menachem Begin, eventually coalesced with anti-Labour liberals (such as one Ariel Sharon) to form the Likud party, which took power in 1977 with the help of the religious Zionist Mafdal, which up until that point had not been all that radical. That was quickly changing, however, and no surprise that the Revisionists became the natural allies of the religious Zionists as they veered heavily towards the right. Natural allies, yes, but it’s really important nevertheless to understand that the two come from very different places. The Revisionists’ founding father, Ze’ev (originally Vladimir) Jabotinsky, was a secular nationalist deeply influnced in the 1920s by Mussolini (something that he no doubt came to regret at least a little bit).

The religious Zionists came from a very different place - originally a relatively conservative position on territory, along with everything else. In the mood of messianic hubris subsequent to the “miracles” of 1967 this position was turned on its head and radicalised. If you’ve got a spare couple of hours, watch the embedded video on the right, for a history of all that, If you do watch it, pay special attention at 23:40 to what Moshe Halbertal says about messianism in the State of Israel being a direct injection of nineteenth and twentieth century European nationalism into the core of traditional Judaism. There’s a LOT to think about there. If you’re not going to watch that film, here’’s the story in a nurshell. The radicalisation of religious Jews was fomented in no small part by the aforementioned Rabbi Kook Junior, and driven on by the Gush Emunim (“Bloc of the faithful”) movement founded in 1974 by his students, most notable among them Moshe Levinger. Rather than following the traditional orthodoxy of waiting for God’s intervention to bring the Messiah and redemption for the Jewish people, these people now took it into their own hands to bring about the redemption. Back to the Book of Esther: don’t wait for God’s providence; do it yourself. This is the ideology which Benny Elon is presenting in this early scene in the film. It’s scary, but it’s intellectually coherent, and that terrifying logic based on a founding document (the Hebrew Bible) is very much at the centre of its power.

This is a film that you have to watch really closely. It was only upon watching a second time that I realised Benny Elon actually appears twice, here as described and in a really important scene not very long before the assassination, when Amir has very obviously made up his mind. No spoilers about what exactly is spoken of in that scene, but it wouldn’t matter too much if I did spill the beans. The main thing to know is that Elon is not the only character that you see more than once. It’s unsurprising, really - obviously we’re talking about some very tight and quite literally conspiratorial circles.

Soon after the scene with Benny Elon we see Amir driving through a rainy night to attend Baruch Goldstein’s funeral. Neither in this scene nor in any other is there any moment where Amir appears to see himself as an annointed successor to Goldstein. What we see from him, rather, is a cold rationality that is interpreted by those on the Israeli religious right who still praise him today as that of a clear minded visionary, but which could equally well be interpreted from a critical viewpoint as the calculation of a psychopath. Let’s just say that in Amir’s exchange later in the movie with Benny Elon, one might have the impression that it takes one psychopath to know another.

We then see Amir presenting Nava, a fellow student who he is courting at Bar Ilan, to his parents. I talked about the complex kaleidoscope of identities within Israeli society in an earlier post about God’s Neighbours, so I’m not going to go over all that ground. Suffice to say that it was a problem that Nava was Ashkenazi, while Amir’s family were Yemenite. The relationship didn’t work out, and Amir fell into a deep depression. It’s not fully understood how much influence this had on his final decision to carry out the assassination., but we can of course speculate. I’m deliberately leaving out one subsequent detail here, which would be a bit of a spoiler - I’ll leave you feeling teased about that. Presumably there is a psychologist’s report about what motivated him, and I would guess that it’s a report which perhaps not so many people have ever been permitted to read. More broadly on the subject of his psychology, we do see quite a lot of Amir’s relationship with both of his parents, and it’s pretty obvious in the movie at least where he gets it all from! His dad is one of the few genuinely likeable characters in the whole two hours. Poor man that he had to go through all that.

Yigal Amir did not of course act alone. He wasn’t a lone wolf directed merely by the words of Benny Elon and the other far right rabbis that we see in the film. His brother Hagai and friend Dror (both of whom we see in the film) were convicted for their compicity in the plot, along with one other (no spoilers). But that was it. Benny Elon went on to be elected to the Knesset in 1996, and served twice as a minister in Likud-led governments, and of course none of the other rabbis were tried either.

Unless some names were changed, or details altered for possible legal reasons that I’m not aware of, there are of course no fictional characters or events in this film. Six years of research went into the movie. That sounds pretty thorough to me, but of course I don’t know enough about the details to comment any more than that. There are several recurring characters in the film that are not played by actors: Yitzhak Rabin is one of these, of course, speaking for the cause of peace. And on the side of the incitement implied by the English title, we see Ariel Sharon and Mr Benjamin Netanyahu. I was in West Jerusalem in September 1993, and I very clearly remember stumbling along with an Irish friend into an improptu right wing demonstration. This cannot have been much more than two or three days after the announcement of the Oslo process. We thought it was rather funny in its apparent amateurishness. There was a sound system, and there were guys dancing round to this song, singing Moshiach Moshiach Moshiach……🥳 But I know now that it wasn’t funny at all. And Bibi was there that night, from the start, inciting the zealots.

Ariel Sharon finally keeled over one day after one too many Viennese cutlets, one too many crèmes brulées or one too many cigars (all of the above, most likely). It’s hard to find very much that is good to say about Ariel Sharon’s influence on Arab-Israeli relations (see my last post), but we do have to admit that he moved at the very end of his political life towards some measures (nowhere near enough, but measures nonetheless) that were looking for solutions. Bibi, however, has built his whole career (and his secret stash of cash, wherever that is) on being the guy who can be relied upon to say no to everything. He can also be relied upon to double and triple down with his hardline rhetoric, the harder things become for him personally. In this embedded video we see him using the language which is currently up before the International Court of Justice in South Africa versus Israel.

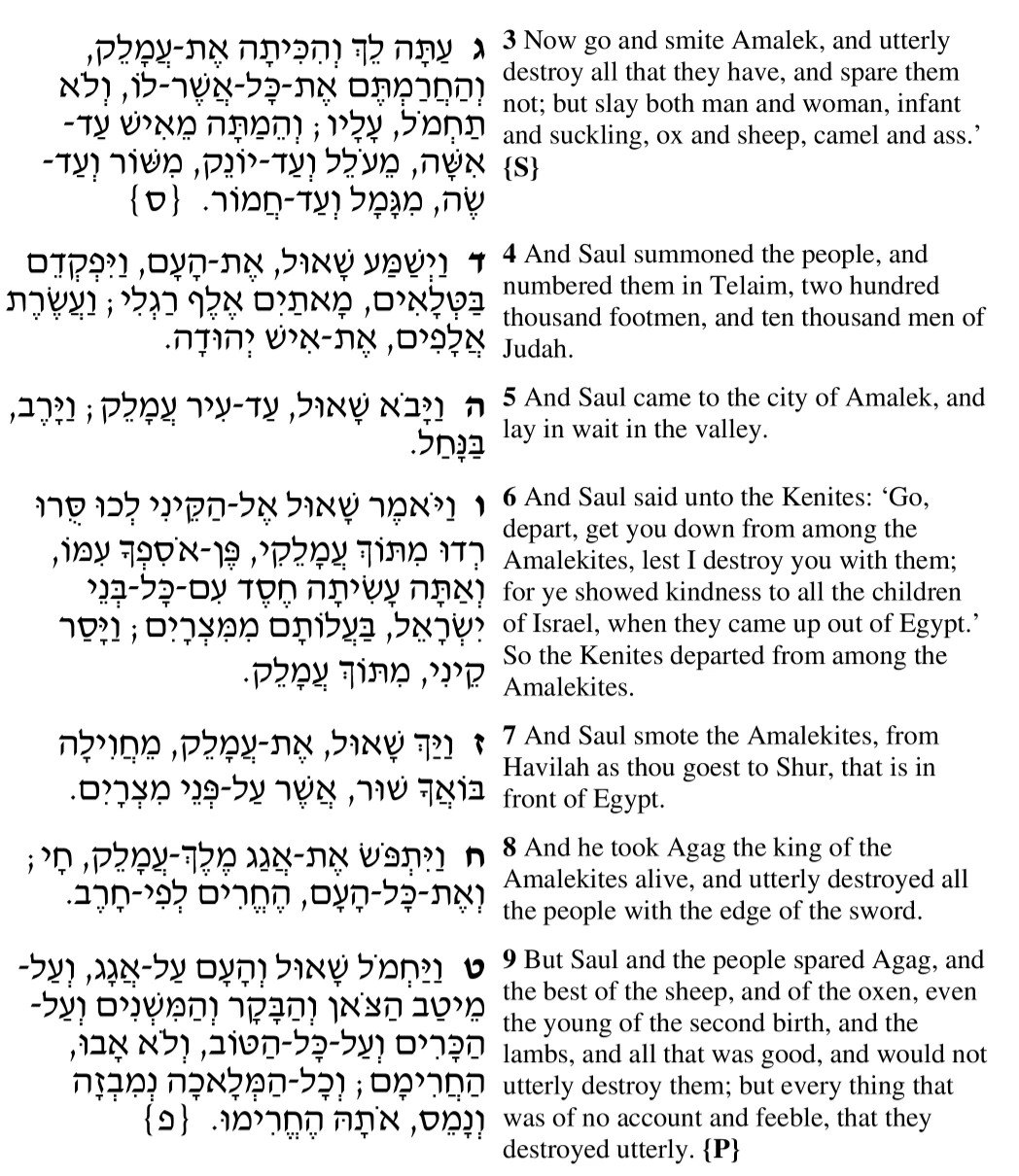

Here’s the language, in its original context, I Samuel, ch. 15, v3-9: (small print, I know, if you’re reading on the phone - rotate the screen to see properly :~)

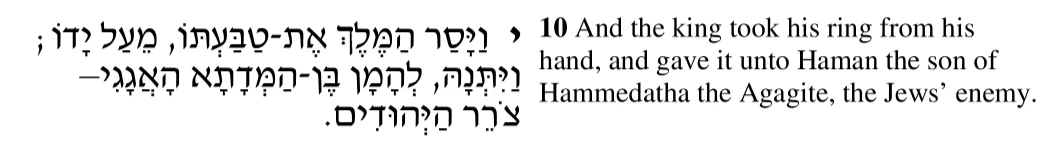

I was originally going to embed this video, which contains a detailed discussion of the meaning of the words used. Initially I was nodding along with the guy, but after a couple of minutes I started to feel uneasy, and then he mentioned comments made against David Irving as if he were a harmless historian/trainspotter, and and not a notorious Holocaust denier who lost a libel trial that he himself brought on the matter. That just goes to show how carefully you need to pay attention to where people are coming from, but anyway it is useful to follow the line of what the man says up to a certain point. As we see in verses 8 and 9, after smiting all those Amalekites, Saul goes a bit soft and lets off Agag., their king And this brings us right back to the Book of Esther, and Purim. Check out Esther 3.10:

So Haman is said to be a descendant of Agag, the guy who Saul spared after smiting the rest of the Amalekites. The lesson learned from this is that Saul made a big mistake, and should have made sure to finish them all off. The night before he committed the massacre in Hebron, Baruch Goldstein listened, in the same Hall of Abraham that he passed through the following morning, to a reading of the scroll of Esther, and was heard to speak of the need to behave like Esther. There may well be more than one interpretation of what he meant. Once again, I leave that for the reader to ponder.

As it is, I am finishing this post off in the very very late small hours of the morning of Purim. I’ve been checking the news while writing, and so far there’s no preemptive strike in Southern Lebanon or even Iran, God forbid. But we must remain watchful until this day is out. I seriously wonder if it’s any coincidence at all that Bibi’s puppet defence minister, Yoav Gallant, has been flown over to Washington for “talks” today. I wonder. I really wonder whether he was given the choice, and I really hope I’m wrong to fear the worst today.

After so much serious talk, it’s quite a relief to be able to provide a Shtisel addendum to this post. While it seems to be difficult to find much information in English on most of the actors in this movie, this is not the case with Daniella Kertesz, who plays Nava. Here she is in Shtisel, playing Raheli, Akiva’s mysterious and fiery love interest in the third series. She’s a tricky one. Akiva never really makes it easy for himself!

You may also have seen her in the Hollywood maladaptation of World War Z, in which she plays the Israeli soldier Segen who is tasked, if I remember correctly, with getting Brad Pitt out of the Promised Land and to WALES. She’s also in Autonomies, which I mentioned in a previous post, but it’s now already getting to the point that I don’t remember which post that was, sorry :~)