Lebanon :

Geopolitics and Invasion

And we’re back! The original intention was to put out a couple of posts every week, but there’s been a looooong delay. I fell down a Lebanese rabbithole. Thankfully I didn’t stay down there as long as those Western hostages that I mentioned in a previous post. They spent the second half of the 1980s locked up in garages and cellars in West Beirut and the Beka’a Valley. Nothing so bad in my case, but once I had seen a couple of Lebanese films, I felt like I needed to find quite a few more in order to do a proper job of these two complementary posts. I have three films to write about here, and in the continuing interest of scrupulous balance the accompanying post discusses three Lebanese-made films about the devastating effects of the Civil War on that country. I’ll come back to the other Lebanese films at a later time. Although I’m also talking about three films here, and there is of course a certain amount of history that I need to dive into, this post will perhaps be not quite as long as the Lebanese-focused post. That’s quite a good thing, because I am conscious of the fact that I’ve probably written quite a few more words up until now in the posts about the Israeli films that I’ve watched. Hard to avoid, because I just have a bit more background knowledge for those, but anyway I think that I’ll be redressing the balance a little bit here.

The format here is very simple. I’m going to discuss three Israeli films about the invasion and occupation of Lebanon. These three films were actually made remarkably close to each other in time. The chronology of the films’ production is in reverse order of the moments in history that they describe. Lebanon, made in 2009, depicts the first days of Israel’s invasion and advance on Beirut in 1982. Waltz With Bashir (2008) is a non-fictional account from an Israeli who was himself in Beirut in 1982. In Beaufort (2007) we see the final stages of Israel’s protracted withdrawal from Southern Lebanon in 2000. There’s a gap of 17/18 years between the events in Waltz With Bashir and those in Beaufort. Why no film from the late eighties or mid nineties? The answer is that there may well be films that I’ve missed from those years, but that the most dramatic events, from the Israeli side at least, were in 1982, and then of course the moment of withdrawal, whether in defeat, victory or something in between, is always likely to be occasion for drama.

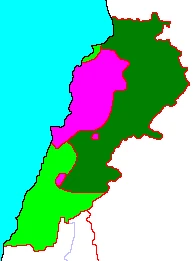

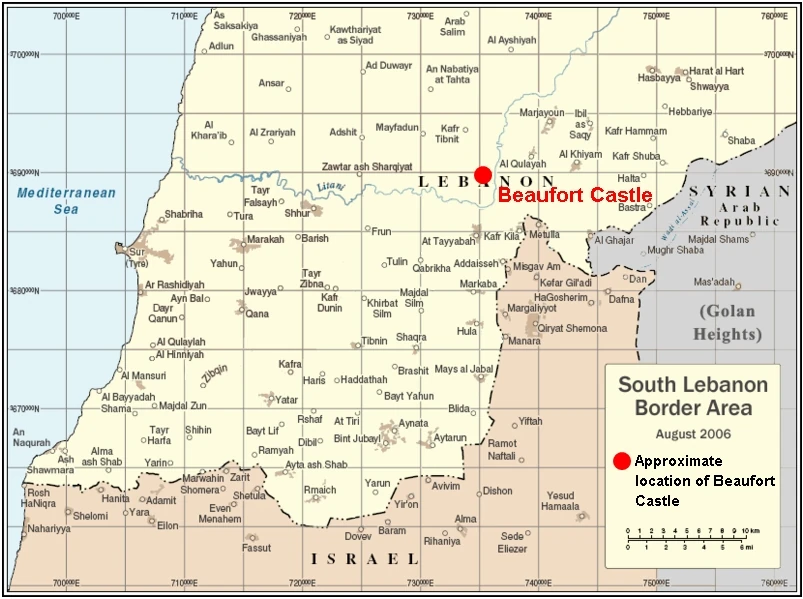

Before looking at the first film, a little historical background. I have little intention here of justifying or decrying anything. The only intention in this first section is to answer the question of why Israel went all the way to Beirut in 1982. Let the films state the morality of the case and of the events that ensued; and even apart from the morality, whether any of that was worth it in the end. Let us first look at a map of Lebanon in 1976, to see the state of play before Israeli intervention. Dark green represents the territory controlled by Syria, under the guise of the so-called Arab Deterrent Force, which also included a few token Sudanese, Saudis and Libyans. Pink/purple represents the areas controlled by the Lebanese Army and Christian militias. Crucially for these purposes, the light green shows the areas controlled by the PLO and its allies. These areas were of course used by Palestinian fighters for shelling and for attacks inside Israel.

June 6th 1982 was hardly the starting point of Israel’s intervention in Lebanon. This dates back to the Coastal Road Massacre of March 1978, when Fatah militants landed on a beach approximately half way between Haifa and Tel Aviv, and then hijacked a bus on the Coastal Road. They proceeded to kill 37 and wounded 76 before themselves being killed in a firefight with the Israeli forces. The Coastal Road attack precipitated the first limited Israeli incursion, known as Operation Litani because the aim was to create a security buffer up to the River Litani, in order to prevent further PLO incursions.

Let’s in fact go back a little further, and note that the opening scene of West Beirut, which takes place on April 13th 1975, shows an aerial dogfight over the skies of Beirut between what I assume to be Israeli and Syrian figher jets (if I’m off-base with that assumption, and one of them is Lebanese, comments are most welcome). This is an early warning, as it were, of the way that the conflict between Israel and Syria, whose lines had been frozen at the armistice that ended the 1973 war, was transferred onto Lebanese territory. There are so many ways of looking at the conflict in Lebanon, and in the accompanying post I was trying to explain the complexity of that country, with its kaleidoscope of communities. In this post we’re zooming out to a colder geopolitical level. Israel and Syria, as the major military powers in the Levant, essentially continued their war against each other in Lebanon, sometimes in direct combat with each other, but more commonly by means of their proxies among the dozens of militias. Israel allied mainly with the Christian militias, and Syria allied with whoever was useful at the time, whether that be Palestinians, Druze, Sunnis, Shi’a, and even some Christians. It’s dirty horrible stuff, and of course if we zoom out to the higher level, the filthiest level of all, Israel and Syria can in turn be seen as proxies for the superpowers at that time, of course referring here to the United States supporting Israel and the Soviet Union in support of Syria.

Between 1978 and 1982, known to historians of the war as the second phase of the Lebanese Civil War, ceasefires came and went, but Israel’s position, in alliance with the South Lebanon Army, did not in essence move from the Litani. On June 3rd 1982, Israel’s ambassador to the UK was shot outside the Dorchester Hotel in London by three men belonging to Abu Nidal’s extreme Fatah breakaway group. He survived the attack, but this was the catalyst for Operation Peace for Galilee, which most reasonable historians believe to have been long since planned out by Defence Minister Ariel Sharon and his Chief of Staff Rafael Eitan. Indeed, the signal of intent had already been sent out in the election campaign of June 1981, in which the incumbent Prime Minister Menachem Begin effectively admitted that Israel was arming the Christian militias in Lebanon, and was therefore functionally in alliance with them. Begin’s right wing Likud-led coalition just barely squeaked to victory over a resurgent Labour Unity platform under Shimon Peres. Whether or not the admission of intent in Lebanon was a net electoral positive or a negative for Likud is not necessarily clear, but once the intention was admitted, Begin was effectively given the green light by his own electorate. As to whether the invasion was approved and rubber-stamped in Washington, that is a question which is hinted at, but not unambiguously answered, in the Hollywood political thriller Beirut, which I mention in the twin post. The eternal assumption that Israel acts as a proxy, a surrogate colonial state, for Uncle Sam in the Middle East has been thrown into doubt time and again by its (Israel’s) unilateral actions over the years, and yet the assumption remains that the two act in lockstep. The assumption is rather lazy, and you don’t need to be approving of whatever they do to say that it deprives the Israelis of their own agency. I’m really not at all saying that it’s a wonderful thing that they do act independently, because they very often tend to do the most irresponsible and counter-productive things (more on that later, but you only need to look at them right now anyway). I don’t even know who I’m defending here. Am I defending both Israel and the US, or am I defending neither? Hard to say, but probably the latter. Just saying that maybe it’s a bit more complicated than saying that the dog wags the tail or that the tail wags the dog. Maybe both, and maybe neither, and what is certain is that you won’t understand it right if you get too emotional about it (easy for a coldblooded Brit to say, I know).

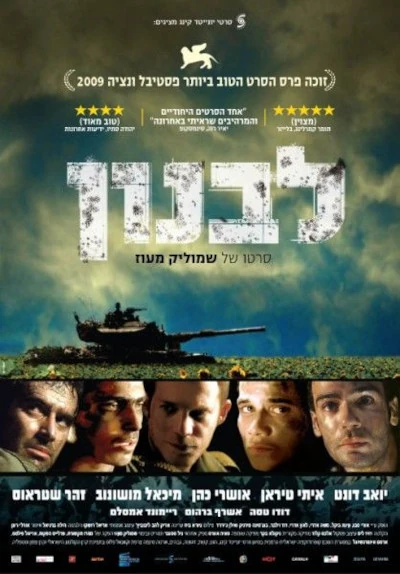

Time for a movie, finally. Who’s seen Das Boot? (come on, IMDB, nobody calls it The Boat!). Das Boot is the greatest World War Two film, in my opinion anyway. It takes place almost exclusively inside a German U-boot in the Battle of the Atlantic, and is the most extraordinarily claustrophobic but also exhilarating war films that I know. I’m not aware of anyone in my family serving in the British navy during the war, but even if that was the case, the power of Das Boot was that I ended up totally identifying with the crew of a U-boot. While Das Boot does have a few scenes outside the submarine, Lebanon goes all the way to the logical extreme of this format. The entire action of the film takes place inside an Israeli tank, making its way towards Beirut in the first day(s) of the invasion. The film begins with a new and very inexperienced gunner, Shmulik , joining the four-man crew. The commander, Assi, and Hertzel, the loader (the guy whose job it is to load the ammunition), appear to be friends, and are joshing with each other as the mission commaences. But unfortunately any spirit of camaraderie or fun doesn’t last too long. The young driver, Yigal, is childlike and jittery. None of them are ready for what is coming.

As far as the plot is concerned, there is no real danger of giving spoilers. We know the history already (and if you don’t, it’s coming anyway). Israel got all the way to Beirut, made a big mess, and withdrew less than a year later. We’re not talking about Dunkirk, D-Day or Arnhem here. We’re not retracing heroic steps, either glorious or tactically flawed. Like all the films in this post, this is most purely an anti-war film, and that is what makes the Lebanon War an important moment in the short history of Israel up to that point. The previous wars had all in some way contributed to the founding mythology of the place, and the Lebanon War absolutely did not lend itself to that.

There’s some of the most deeply affecting imagery that you’ll ever see in any film about war. I’m not going to issue out any spoilers about which images hit home the hardest. I’ve personally got several etched in my memory, and there’s plenty to debate, if you want, about which image is most striking or shocking. After an hour and a half inside that tank with these guys, even if you’re the most pro-Palestinian and anti-Zionist person on God’s Earth, you won’t be human if you’re not caring about whether or not the crew are going to survive, just as I found myself completely on the side of the German U-boot crew. The outcome is immaterial, however. Even if they do survive all the way to Beirut and back, you know that the message of an anti-war film is going to contain awful imagery, that people are going to die, and we’ll be wondering why it all had to happen.

If you haven’t seen the film already you might be wondering how they manage to keep the action “interesting” for 90 minutes from inside the tank. The answer of course is that they can see the world outside the tank, but only through the commander’s sights in the turret and the gunner’s sights. Mainly we’re seeing things through the eyes of Shmulik, the gunner. No surprise, perhaps, if I tell you at this point that the director, Samuel Maoz was himself a gunner in one of the first tanks to enter battle in June ‘82. And there really is enough inagery to haunt you for a good long while. Apart from the crew’s mounting stressful interactions with each other, there are several “visitors”. There’s Jamil, the severe but ultimately not inhuman group commander (more about the actor at the end of the post!). There’s a dead body😬 There’s a terrified Syrian prisoner, and most chillingly of all, the Syrian’s arch-nemesis and the Israelis’ “ally” - a Christian Phalange militiaman, played by Ashraf Barhum, who is going to turn up in several more films down the line, including Farha, Paradise Now and The Syrian Bride.

OK, now watch the trailer, but before that, I want to comment about the trailer for the movie on the IMDB site, which contains the comment on the right, from a reviewer. Plenty of thrills??????? Seriously, Eric Kohn????? Did you feel like a five year old riding a tank on a fairground ride? I can think of lots of -ing adjectives to describe this film - depressing, distressing, disgusting, disturbing, perturbing, provoking, heartbreaking, gut-wrenching, tear-jerking, harrowing, agonising, exhausting, tormenting, excruciating…. But thrilling would be a very poor choice of words. Very poor indeed, Eric Kohn, even if you were on a tight deadline and your words have been ripped out of context.

It took little more than a week for the Israelis to reach Beirut. They had originally been under the impression that the Christian militias would be undertaking the role of fighting and pursuing PLO fighters in West Beirut, but it became clear to them that the Christians did not intend to do so. Knowing that if they went in to the city the number of casualties would be unacceptable for the public back home, the Israelis decided to besiege the city. Food, water and electricity were cut off, and Israel was meanwhile widely criticised for using imprecise and indiscriminate shelling, ordered by one Ariel Sharon. Needless to say that more civilians were killed than PLO guerillas. Plus ça change……._ After two months the Americans brokered an agreement that the PLO leadership would be granted safe passage out of Lebanon, under the protection of an “international” (that is to say Western) peacekeeping force.

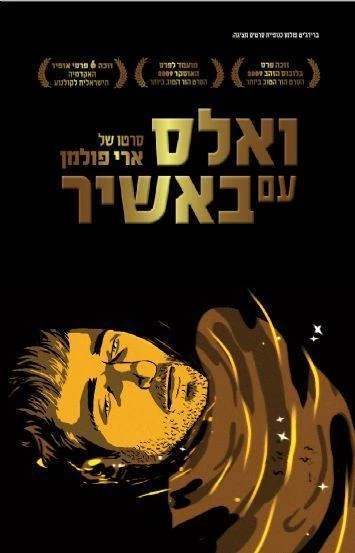

What happened next is the subject of Waltz With Bashir (ואלס עם באשיר). Unsurprisingly, it’s a pretty touchy and taboo topic to this day in Israel. Numbers will probably never be known, but the facts are clear beyond doubt. On September 14th 1982, only a month after the PLO’s departure with the peacekeepers, Bachir Gemayel (the Bashir of the title - I’m using the French spelling here, in the Maronite way) was assassinated before officially taking office as the newly elected President of Lebanon. The man responsible for the assassination turned out later to have been a Christian member of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party (the list of these parties never ends….), BUT in the wake of the assassination it was immediately assumed that it had been a Palestinian mission. Cutting a very long story short (read the details about it here on Wikipedia, in Robert Fisk’s history, or wherever else), the decision was now taken to go into West Beirut, something which had previously been avoided and was in breach of the agreement negotiated with the USA. The green light was given by Ariel Sharon and his Chief of Staff, Rafael Eitan for Christian militias to enter the two Palestinian refugee camps, Sabra and Shatila. I’m not going to speculate in detail about Sharon and Eitan’s motivations, but unfortunately my gut tells me that it’s only ever about revenge in the Middle East (please excuse the sweeping statement), and for sure the Christian militias were up for a bit of that. From September 16th to 18th the Phalangists ran amok in the camps, raping, torturing, maiming and killing. Israeli forces assisted them by lighting the camps up during the night with flares and spotlights, and providing bulldozers to clear away the bodies. Estimates of the number of deaths range from 460 to 3500. The dramatic range of the estimates is some indication of the devastation that must have unfolded, and the bewilderment of the first witnesses after the event.

The film is purely autobiographical. Ari Folman, the writer, director and producer, is also the main protagonist. Folman was serving with the IDF in Beirut in 1982, and in the first minutes of the film, which begins with a friend telling him about a recurring dream about Lebanon, we learn that Folman has no memory of his experience there. The following eighty minutes take him on a journey in which he tries to remember what he saw, and of course to understand why he remembers nothing. The film is done purely in the form of animation, apart from the very final scenes. I believe that this was mainly at the request of some of the friends and comrades that he interviewed along the way, who didn’t want to be on camera. Like the performance of Yasser, the Palestinian character in The Insult (see the accompanying post), there’s something very quiet and understated about Folman, and indeed about most of the people that he talks to. The film also has, in common with Memory Box, a bit of early 80s musical nostalgia. Not sure what else to say. I did the history. Like Memory Box, it’s all about the suppression of the memories, and I guess the trailer will say a bit more.

Israeli forces stayed for little more than a year in/around Beirut, but that was long enough to catalyse the total breakdown of what was by then left of Lebanese society. Israel slowly withdrew from central Lebanon (without the reciprocal withdrawal of Syria, which had been one of Israel’s most important expectations), first to the River Awali. In the wake of this first withdrawal, a predominantly Christian-versus-Druze conflict broke out in the mountains of the Chouf district south-east of Beirut. Meanwhile the multinational peacekeeping force, which had come to Beirut to supervise the PLO’s departure and had then returned only after the Sabra and Shatila massacres (damning its mission from the start in the eyes of the population of West Beirut), was driven out by the Islamic Republic of Iran’s first and certainly not the last major involvement in Lebanon - a humongous bombing. That bombing dominated the news in the West for days, if not weeks. Without the peacekeepers there was now no central authority whatsoever. The Lebanese army collapsed into factions, and permanently lost control of West Beirut to the Shi’a Amal militia (those last words echo in my mind) and the Druze Progressive Socialist Party. This was the moment when Westerners started to get picked up on the streets of Beirut, and the group that was responsible for many if not most of these kidnappings was Islamic Jihad, a group funded by Iran, which would eventually fold into what is very much up until this day Hizbu’llah (or Hezbollah, depending if you want to go with the Arabic or the Farsi). At this point Beirut is already a long way off in the distance as far as the Israelis’ involvement in the history is concerned. Once Israel withdrew in 1985 back to more or less the same line that it had taken up in 1978, the following fifteen years were spent fighting alongside the Christian South Lebanon Army against the aforementioned Hizbu’llah, which was declared into existence on February 16th 1985, and is still going strong (stronger and stronger, it seems). This conflict in the South continued despite the fact that the Civil War in the rest of the country had come to its bitter, tired conclusion in 1991. And who emerged strengthened from the Civil War, if it wasn’t the Palestinians or the Christians? Answer: the Shi’a militias, with the support of Syria and Iran, and especially Hizbu’llah, which had carved out a state within the state. Bear in mind that the majority of the population of South Lebanon is (and I believe always was) Shi’a. Hey Presto! Israel went into Lebanon to fight a Palestinian enemy armed and funded by the Soviet Union, Syria and other Arab states. Having cleared out that enemy, Israel withdrew and found itself, to this day, facing an enemy armed by Iran, Syria and now of course (no joke) Russia and China. So what was achieved? I’ll leave the obviously rhetorical question hanging.

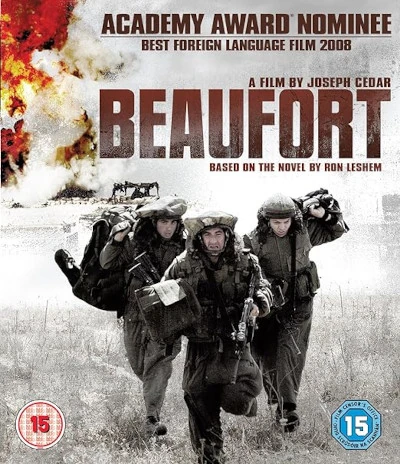

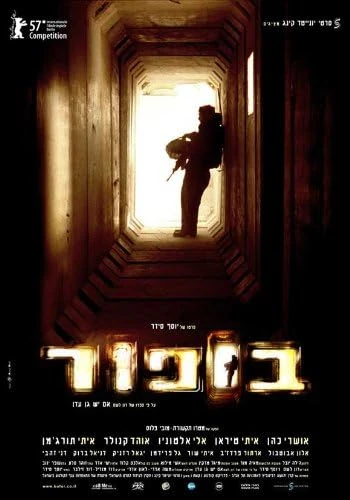

Fast forward from 1982-85 to the year 2000. Having clearly spoken in favour of withdrawing from the attritional conflict in South Lebanon during the election campaign of the previous year as part of a wider attempt to bring a final peace settlement with the Palestinians and the Arab World, Ehud Barak’s cabinet has voted in favour of a full withdrawal. The South Lebanon Army has crumbled and its leaders are now seeking asylum in Israel. Beaufort, the site of a ruined Crusader castle in Southern Lebanon, is one of the few remaining strongholds in Israel’s line of northern defence, and certainly one of the northernmost. Beaufort, the film of the same name, takes place exclusively on the hillside, and in the vast fortified complex of tunnels built into the mountain. The film was made in 2007, ironically (or maybe intentionally?) one year after Israel went back into Lebanon (albeit for just one month and not 22 years) in 2006.

No spoiler, then, if I say that this film is set in the last days and weeks before the Israelis withdrew from Beaufort, and that it’s a film all about waiting - waiting to finish guard duty, waiting to get home, waiting to withdraw - and of course hoping - hoping not to get killed. There’s a fair bit of the same nihilistic humour that I talked about in Zero Motivation, but of course by contrast with that movie the enemy here is very real indeed, if not visibly present. There is also the very interesting observation of a quite formal separation between the secular and the religious, even in such a place where you’d surely think that group solidarity should be essential. Not surprising to see this - it’s a thread running through the work of this director, Joseph Cedar, who is possibly my favourite Israeli director (albeit I’ve massively appreciated both of the films that I’ve seen by Samuel Maoz). I’m going to be talking about several more of Cedar’s films, each of them quite different from the other. Frustratingly, I’m having a lot of trouble finding Campfire., other than buying it at great expense from the US eBay. If anyone knows how to find it somewhere, please let me know.

Warning - I’m going to say something which may sound a bit pretentious about my impressions of the first few minutes of Beaufort. OK, it sounds pretentious, but it’s really not, because it’s just what I was thinking. The bunkers in Beaufort totally made me think of the space station in Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (this is the superior Soviet 1972 version that I’m talking about, eh - not that George Clooney crap). Looking now at the screenshot of Solaris that I’ve just added here, I don’t suppose that there is much resemblance at all. It must have been much more about the mood created around the warrens in each case. There’s always a reason for these things. I’ll have to watch both of them to figure that out.

Just one more note - two of the actors in this movie are also members of the Lebanon tank crew. Oshri Cohen, pictured right, plays the bunker commander Liraz, and is also to be found two years later (or eighteen years earlier) playing Hertzel, the loader/ammunition guy in the tank. There’s also Itay Tiran, who in this movie plays the medical technician Koris, is Assi the tank commander in Lebanon. Tiran may also be known to some British readers for his appearance in a British TV series called The Promise, which is one of very few films or series kicking around which talk about the British Mandate in Palestine. In the series he plays an Israeli in the present day who has become a bit of a black sheep in the family by questioning the legitimacy of the State of Israel. Basically Tiran is playing himself there, because he is an interesting case study of a third/fourth generation Israeli who has become deeply disillusioned with the way Israel is going. No doubt he’s very much a symbol of hate right now in Israel, and probably some readers from both sides will have strong views about his activism. I’m not getting involved with any of that here, whatever I may or may not think about it. You can read a bit more about him here.

OK, and now go ahead and watch the trailer. I know that you probably have already.

Before the Shtisel addendum, I’m going to finish this post with a personal note. The picture that you see below was taken on the far northern border of Israel, in 1994. The friend on the right recently got in touch with me after a veeeeeeeeeeeery long disappearance, and while nostalgising over many things in the last weeks we were trying to remember exactly where this photo was taken. I knew that it was very close to the Lebanese border, and successfully narrowed it down by working out that the ruined Crusader castle in the background is Montfort (very original names those Crusaders came up with!!) We were visiting the friend on the left on a kibbutz, but I had absolutely no recollection of the name of the place. I’m usually the one with the memory, but it failed me on this one. The working hypothesis (based on my friend’s memory) is that our friend on the left was living on Kibbutz Adamit, but it’s yet to be confirmed at the time of writing, and I just want to say that if anyone recognises the chap on the left (or even if Yaakov recognises himself!!!) it would be very nice to get a wave ✋

For reasons that are, I think, pretty obvious since 7/10/2023 Adamit is currently not occupied by its inhabitants. That northern stretch of territory is under pretty regular shelling right now, and even if it wasn’t I don’t think that I would be sleeping well if I happened to live there. I honestly don’t remember even once asking if it was safe when I visited that time in 1994. Young and still quite clueless as I was, maybe it just didn’t occur to me, but maybe it really wasn’t especially unsafe at that time. Obviously that’s not the case at the moment, and for the foreseeable future, and I’m afraid that I’m forced to ask what that tells us about the achievements of Israel’s 22 years in Lebanon. Does somebody, maybe Mr Benjamin Netanyahu, ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha, have a plan to end the bloodshed and endless cycle of violence? Or is the plan only to try constantly to keep the enemy off balance? If it’s the latter, let’s state the obvious. There’s more of them, and inevitably in any conflict, even if it goes on for more than a hundred years, I guess that there’s a point where one side gets really really tired. I just question if Israel is at all balanced right now, and I fear that not even God knows what will happen if things get really hot on that northern border. I assume that the current occupants of Beaufort aren’t using it for historical tours.

Although there are three films here, there’s only one Shtisel addendum. Surprisingly, perhaps. But then again, Waltz With Bashir was a cartoon documentary, so zero chance of meeting anyone there, unless they also happened to have been in Beirut with Ari Folman. In both Lebanon and Beaufort, however, we do have one Shtisel stalwart. Zohar Strauss plays Jamil, the hardass group commander, in Lebanon and has a small cameo role as a visiting senior officer in Beaufort. In fact he’s surely going to be in the running for the actor on the Israeli side with the most appearances in these films. He’s also in The Cakemaker, and maybe some others that I’m not remembering right now. Saleh Bakri is almost certainly running away with the overall title, but there has to be a competition on both sides, for balance 👐

While he’s certainly not playing the most sympathetic chatacters in either Lebanon or The Cakemaker, in Shtisel he’s easily one of the most lovable. Lippe Weiss is the husband of Giti, the Reb’s daughter, and he spends the whole of the first series (and a good part of the second, if I’m remembering correctly) being cold-shouldered by his wife, and publicly shamed by his daughter (!!!!) for having briefly lost his faith and fallen off the Haredi wagon. Not sure if I should give spoilers for Shtisel, but anyway the good news is that he does eventually find a way back into the affections of both wife and daughter, because he’s a really good bloke.

A MUCH LATER ADDENDUM

Approximately half a year has passed since I first posted this. Let’s not say that I saw it all coming, but I suppose I had a fair idea that it was more than possible, alas. So here we go again, and here’s a very obvious reaction for anyone who’s into cult TV and cinema:

(Head in hands - not that history exactly repeats itself or even rhymes, but like a Biblical parallel couplet, one moment resonates with another.)