Lebanon :

Pandora

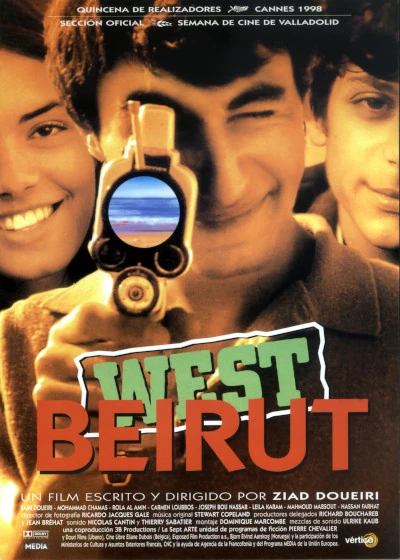

Made in 1998, West Beirut may well be the first Arab language film that I ever saw. And if you’ve read a few of my posts and worked out my age by now, you may well ask what took me so long, given that I had been studying the Middle East for a few years already. The answer is just that I didn’t watch so many films in that time - certainly not if they weren’t European or American. In the defence of blog balance let me add that I’m also pretty sure that I didn’t see any Israeli films until around this time. Maybe Kadosh was the first one (that’s for another post).

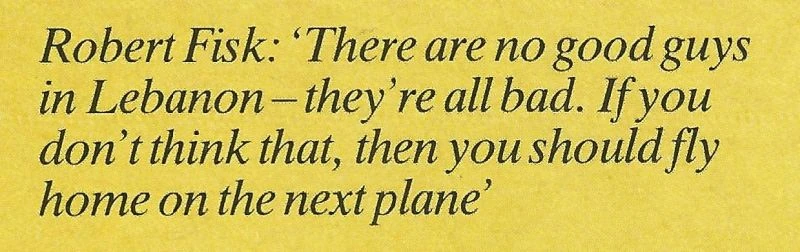

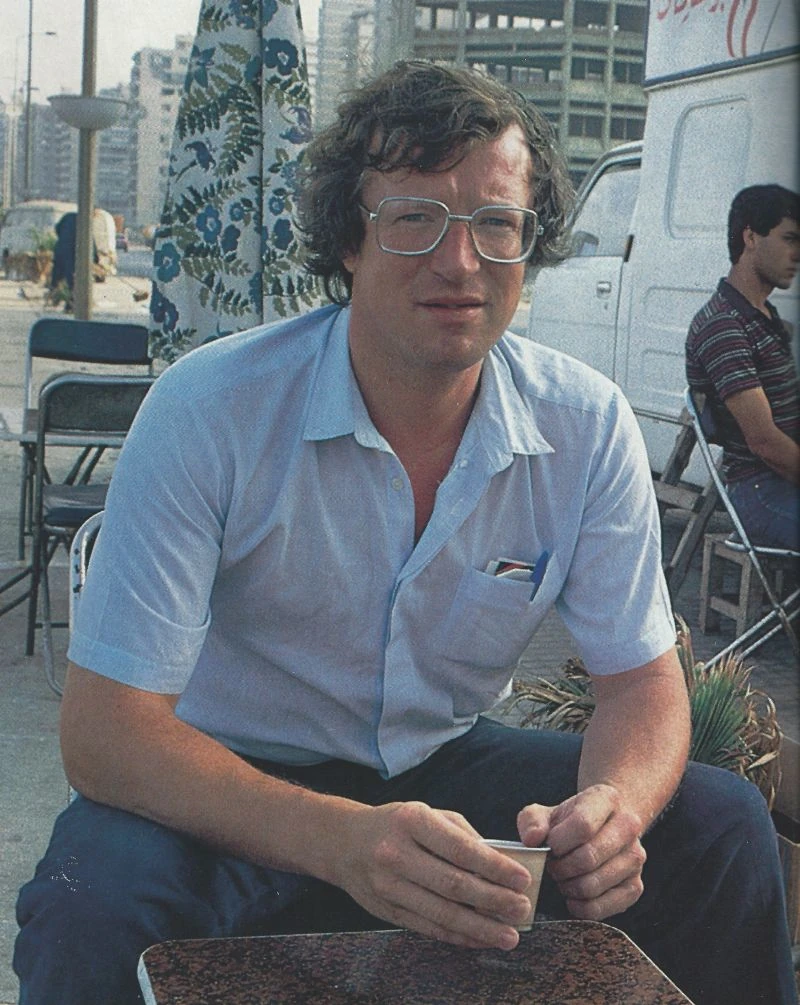

West Beirut was quite the epiphany for me. Having for many years mentally pictured Beirut as a giant urban mantrap, with perfectly good reason given all the news that we were fed about the place throughout the 1980s, it was virtually impossible to visualise the lives of ordinary Lebanese people in the midst of the madness that engulfed them for fifteen years. As I mentioned in my previous post on Costa Brava, Lebanon, there were times between 1986 and 1990/91 when Western hostages in Beirut seemed to be mentioned in the news pretty much every day. It could well be that that’s a false memory of mine, revealing the extent to which I was already sucked emotionally into the Middle East Vortex, but then again it may also be accurate enough. The point, anyway, is that the only Lebanese that we heard about during that time were the Gemayels, Michel Aoun, Nabih Berri, Kamal and then Walid Jumblatt, and the dozens of militias, Sunni, Shi’a, Christian (Maronite, Orthodox, Catholic…), Druze, Palestinian, Lebanese Nationalist, Lebanese Communist, Pan-Arabist Ba’athist (Syrian-affiliated or Iraqi-affiliated) or Nasserist, Pan-Syrian Nationalist, Armenian, Assyrian (!!!!!)…… mind-bending in complexity, and impossible to commit to memory. It was all just leaders and factions, intervening neighbours and great powers, and there was no room in the discourse to put a human face on any individual Lebanese. The following quote from Robert Fisk, in a commemorative 200-year anniversary colour supplement edition of the Times sums up the cynical attitude that an attuned Westerner developed towards Lebanon (partly his fault for saying things like this):

In his case, I have to give him a pass. This was only the most healthy scepticism, absoluely necessary for the daily survival of someone who was seeing his friends and colleagues killed or kidnapped on a regular basis, and of course we know that he only meant to talk about the militias and their leaders, not about the ordinary people caught up in the tragedy; but as an impressionable teenager that quote hit me quite hard. I somehow took it very literally, and it informed my image of Lebanon for many subsequent years. That, then, is why watching West Beirut was an important moment for me. The film broke down that prejudice. Even just within the title there’s a peculiar resonance for any British or Irish person of a certain age. We precisely had our own story of a city divided between East and West, contemporaneous to those fifteen years of Civil War in Lebanon. There was Irish Republican Catholic West Belfast, and British Loyalist Protestant East Belfast; there’s also little doubt that the IRA of West Belfast had plenty of communication via 1970s revolutionary channels with the Palestinian and then (more tenuously?) the Shi’a militias of West Beirut. This may well have had at least something to do with the fact that the dual national Northern Irishman Brian Keenan was released from his captivity much earlier than the other British and the American hostages (everyone born in Northern Ireland is automatically a dual national, by the way - there was nothing special about Keenan’s status)..

The story of this movie begins on April 13th 1975, the day on which the Lebanese Civil War is said to have officially started. Tarek, a student at the French lycée and a cheeky trouble-maker, has been expelled from his classroom for mocking the French former colonial power first at the school assembly and then in the classroom. While standing at the window outside the classroom he witnesses the second, escalatory massacre of that day, in which 30 Palestinians in a bus were killed by the Christian Phalange militia in retaliation for the shooting of four Christians earlier that day. Of course it didn’t start out of nowhere on that day. The tensions had been building up for months and years, but that is taken by most historians to be the day, if there has to be one day, when it all kicked off. The rest of the class quickly run out to see what has happened, and gawp in horror and excitement. Like the days when I was sent home early from school because of snow, Tarek and his friend Omar are delighted to get out of school, completely failing to process the enormity of what has just happened in front of them.

Tarek and Omar are Muslim, and they live in West Beirut, I’m not sure whether they’re Sunni or Shi’a, The posters in the neighbourhood suggest Shi’a, but I just don’t know enough about the demographics to be sure whether Sunni and Shi’a would have been living together in the same districts in 1975. Be it Sunni or Shi’a, the fact that they are Muslim means that they are unable to get back to the lycée the next day, because the Christian militias have already set up barriers across the city, and the Palestinians and other Muslim militias have reciprocated. The lycée is in the Christian East, and no-one with Muslim ID (presumably it is/was shown on Lebanese ID cards) is allowed through. While Tarek’s parents worry about what is coming, his mother correctly fearing the worst and his dad hoping for the best, Tarek and Omar are in teenage fantasy land. Schoooooool’s out, FOR EVER….

The following ten/fifteen minutes show the two teenagers emjoying their lazy paradise. There’s a massive dollop of seventies nostalgia here, to remind us of what life was life for well-to-do middle class people all over the world at this moment in history, when Lebanon was wrenched out of all those normal developments that the rest of us went through. There’s a soundtrack from this classic seventies hit, which you can find to the right here - a song that was so popular at the time that EVEN MY MUM used to sing it to me. Tarek and Omar are also into making movies (presumably this is a bit of personal autobiographical nostalgia from the director) with Omar’s Super-8 camera, which they sneak into places where it’s not meant to be, like a good pair of normal teenagers.

There are a million more things to say about the amazing beautiful ordinary Lebanese characters in the movie, but rule #2 of this blog is no spoilers.. My favourite cameos are the fabulously profane shouting cursing lady in Tarek’s block of flats, and the sweet old dude in the bakery. There is a love interest, and wouldn’t you know it - she happens to be from the other side. Other than that, I think that it’s not really a spoiler, for anyone who’s heard more than ten words in their life about Lebanon, to reveal that things don’t get better after those first few moments of freedom from school. Tarek, Omar and May, the love interest, have several more adventures, including one in which they cross the Green Line (and if I tell you where they end up it’s a spoiler). But since these events are clearly happening over a span of two or three years (a later scene takes place at the time of Kamal Jumblatt’s funeral, nearly two years after the war began), we are skillfully shown the teenagers’ adventure degenerating into anxiety, terror and despair. It’s sad. It’s tragic, but it’s a really really really beautiful film, and so important to watch for anyone who wants to understand all this.

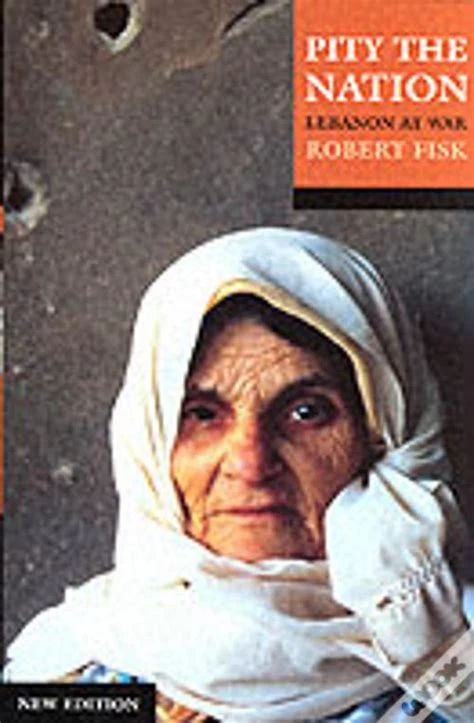

For anyone who knows next to nothing about all this, it may be necessary to add a little background history here. How and why did this awful war come about? Well, it would be hopelessly ambitious to try here to retell all the events in the Lebanese Civil War. I’m only here to encourage people to watch these three films, and then to read up about the history if interested. As mentioned in the Costa Brava post, if you want to go into the nuts and bolts you can check out the classic account of the Civil War from somene who saw most of it first hand. Click/Tap on the pic (but don’t buy it from them, ha ha!!!!). The only thing that I can tell you now about reading Robert Fisk’s book nearly twenty years ago is that I feel I now need to read the whole 700 pages once again, from cover to cover, because it was impossible to retain even a fraction of the information. For the purpose of this post, I’m revising by reading up on Wikipedia, which is OK, because I’m not trying to be either an academic or a journalist here. However, I do have to say that some sections of the very very long article on the Civil War are not especially well written, so it might be confusing for beginners. I’ll try to summarise the fifteen years in a few paragraphs. Hopefully not too long, but hopefully enough to get the idea of what’s going on in the three films (I’m coming to the other two later, obviously), and any further questions are welcome in the comments, I guess. But mostly I just encourage anyone to go away and read about it. It takes time and patience to understand.

The reason that most roads to understanding the Middle East run through Lebanon is that most groups that contribute to the complicated patchwork of the Middle East are to be found in that small mountainous strip of land. You’ve got several flavours of Christianity, all represented in some reasonable numbers (even a few Protestants), but the Maronites predominate (follow the links if you want to understand who everyone is - there are too many rabbitholes to go into detail). You’ve got Sunni and Shi’a Muslims in approximately equal numbers (at the start of the Civil War, at least - the Shi’a numbers have gone up over the years, and that was in fact one of the many causes of the war - see below…). This is not to say that you would necessarily find all versions of Sunni or Shi’a in Lebanon. How many Sufis or Salafis are there, I have no idea, nor whether the Lebanese Shi’a lean more towards Twelver, Ismaili, Zaydi or any lesser known version of Shi’ism. You’ve got the Druze, who are quite literally a whole world unto themselves, and then there are significant numbers of Kurds and Armenians, who bring their own compicated refugee politics. There are probably some other groups that I have never even heard of. Maybe there are/were Zoroastrians in Lebanon, for example. And the fact that the world centre of the Bahá’i faith is in nearby Haifa may also suggest that Bahá’is are/were perhaps to be found in Lebanon (I wouldn’t expect them to have remained, however). Go check and tell me if I guessed right. I’m not even going to dive down those rabbitholes.

Without going into too much detail about how the modern polity and eventually the state of Lebanon developed from the weakening of Ottoman rule in the 18th century up to the end of French colonialism in 1946, it should already be clear enough that we’re talking about a very very complex and politically fragile place, highly sensitive to changing demographics. For the approximate thirty years between independence and the outbreak of the Civil War, Lebanon was governed by the National Pact, which ensured Christian hegemony. This was justified by the 1932 census results, which showed the Christian population at 51%. You can read the details by following the link. With a higher birthrate among Muslims, and especially the Shi’a, the 1932 census results soon became very obviously outdated, but Christians refused to allow another census to be conducted. This was one of the many many reasons for the tensions that led to the outbreak of the war. Civil strife had previously been averted on more than one occasion, most notably in 1958, and early on in West Beirut Tarek’s dad also talks about other crises in 1964 and 1973 - rabbitholes which I’m avoiding! The only thing that we need to understand is that by 1975 there was just far too much stored up tension to avoid the explosion of violence.

Now we throw into that mix two groups of peoples that we left unmentioned in the preceding paragraph - Jews and Palestinians.

Needless to say that there were Jews in Lebanon before the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. It wasn’t necessarily an ancient Jewish community akin to those in Iraq or Yemen, but they were there anyway, and of course as life became more unsustainable for Jews in Arab countries after 1948, and especially after 1967, the majority had left either for Israel or Western countries by the early 70s. In the first two years of the Civil War the remaining Jews found themselves targeted for attacks, and after 200 were killed in pogroms (says Wikipedia, anyway….) the majority of that remnant of approximately 1800 people left (totally relying on Wikipedia here - read up if you want to be sure of all this). Remarkably, though, even at the time of the very dramatic and consequential Jewish advent in Lebanon in 1982, there were still a few Jews remaining in Beirut, and a few even remained after the Israeli withdrawal in 1983. As for the Palestinians, they wouldn’t have been in Lebanon if it weren’t for the State of Israel, and the Israelis wouldn’t have been in Lebanon from 1978 to 2000 if it weren’t for the Palestinians being in Lebanon. I guess I need to write at least one more paragraph after all.

Onto the Palestinians, then…… Cheating here - I just started watching one more film, which I’m going to insert before I talk about the other two Lebanese films. This film is (confusingly, sorry!) called Beirut. It’s Hollywood stuff, made in Morocco rather than Lebanon, and it certainly does fall into a few Hollywood clichés about the Middle East. However, I think Jon Hamm is a fantastic actor, and he does a great job as the main protagonist in this decent addition to the Middle East Thriller genre. I’d say that the pace of the film is pretty difficult for anyone who doesn’t have a secure understanding of the Lebanese Civil War, but it’s probably still quite entertaining in a masochistic way even for those who don’t understand the politics. It’s been criticised (gleaning from the Wikipedia article here) for dehumanising, diminishing and even perhaps orientalising the Lebanese and Arabs in general, especially in the trailer. which lifts one line from Hamm’s character’s opening soliloque. The criticism is somewhat justified. I’ll quote the soliloque in full here, and then I’ll comment a little on the other side:

I like to tell people if you want to understand Lebanon, think of a boarding house without a landlord. Okay? And the only thing that the tenants have in common is their talent for betrayal. So these people have been living together, cheek-by-jowl, for 20 centuries. Two thousand years of revenge, blood feuds, vendetta, murder. One night there's a storm. Raining like all hell. There's a knock at the door. Who is it? It's the Palestinians. They want in. They've been up and down the block, doors slammed in their face. They're cold, they're tired. They want in and they want in now. So the house is thrown into confusion. Tenants arguing. Some of them violently opposed. Some of them think, "Let 'em in, they'll be gone by tomorrow morning." Some of 'em think, "If I let them in tonight, then I'll have an ally against my enemy down the hall." Some of them are terrified as to what happens if they keep the door shut. So it isn't until after the Palestinians move in, that the other people in the house realize the tragedy of the situation. That the Palestinians want nothing more than to just burn down the Israeli house next door.

I’m going to agree with the criticism about reducing two thousand years of history to the level of The Godfather or The Sopranos, but hey - it’s 💲💲HOLLYWOOD💲💲, 👶BABY👶, and they have to market their movies the way they know how! Leaving aside the first few sentences, the metaphor of the boarding house is as apt a one as I’ve ever heard, and it’s going to save me from writing at least five hundred words of my own. First of all, let’s recap the basics. The Palestinians came to Lebanon (mainly at least) in two historical waves. The first was in the immediate aftermath of the Nakba of 1948, in which people from the North of the country fled into Lebanon (people in the South of course would have more likely fled towards Gaza or Jordan, but that’s detail that I just don’t know). There was a second wave of Palestinian migration to Lebanon after the Six Day War in 1967, or more precisely after Black September in 1970, when there was effectively a short civil war in Jordan which led to the Palestinian leadership being forced to flee that country. This was the tipping point which made the Lebanese Civil War inevitable (in hindsight anyway). The PLO used Southern Lebanon as a base for attacks deep into Northern Israel, building up the tension on the border, and thereby destabilising the already fragile balance of the Lebanese body politic. So who’s who in that house metaphor? Very approximately, we can say that the Christians are the people in the house who don’t want to allow the Palestinians in at all. Although everyone else got dragged in pretty much immediately, the Civil War started as a straight dogfight between the Christians and the Palestinians, and during the Civil War the Christians were predominantly allied with Israel, the enemy of their enemy. The Druze had beef with the Christians going all the way back to 1860, and so we can say that they’re the people in the metaphor who are keen to induct the Palestinians as an ally against the Christians. As for who out of the Sunni and Shi’a are the ones who are scared not to let the Palestinians in, or who are not too concerned about their presence - not sure, honestly! I guess it was probably a big mishmash. The main thing to understand is that the Christian-Palestinian relationship was the initial flashpoint, and the rest is fifteen years of tragedy from which no-one of course emerged unscarred.

OK, but who “won” the Lebanese Civil War? Let’s start with the sides who definitely didn’t win. Neither of the two sides who catalysed it, the Christians or the Palestinians, won it. Yasser Arafat and the rest of the PLO leadership were famously driven out of Beirut by the Israeli invasion of 1982, leaving the ordinary Palestinian refugees often defenceless against attack, initially and very notoriously of course from the Christian Phalange (but let’s leave the account of that for the accompanying post), but also from fellow Muslims (see, for example, the War of the Camps), who didn’t necessarily turn out to be too much on their side despite the obligatory kalaam faadi (empty words - كلام فاضي) about Free Free Palestine.

The Christians also lost the Civil War. The main reason that Christians feared the Palestinian presence in Lebanon was nothing to do with any deep-rooted identification with the Jewish State. Simply put, it was about demographics. Having been a clear majority of the population of Lebanon at the time of its founding as a state, the Christians had by 1975 become a minority community, along with every other community, and the Palestinian presence had dramatically contributed to that dillution of the demographics. The Phalangists and their allies in the Lebanese army were fighting to reassert their dominance over Lebanon, and in the end they failed. In Memory Box we are introduced to a Christian Lebanese family forced to flee the country towards the end of the war, and in The Insult we meet a VERY angry Christian man, who refuses to let go of his own pain. If I tell you why he’s angry it’s a massive spoiler of something that only gets revealed right at the end of the movie, so I’ll keep it zipped 🤐 Let’s just do a very brief overview of the two films, and then I’ll come back to the question of who won the Lebanese Civil War. If anyone did.

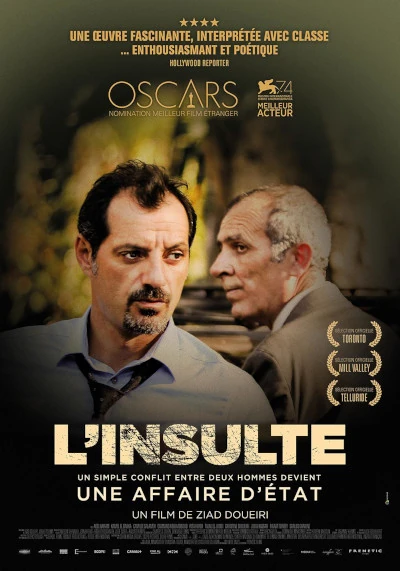

Starting with The Insult (known in Arabic as Case No. 23 - قضية رقم ٢٣ - Qadiyya raqm 23). As the Arabic title clarifies, this is essentially a courtroom drama, set around the time that the film was made, 2017. The film begins with Tony, the first of the two antagonists, attending a political rally of the Lebanese Forces, the largest political party in the Lebanese parliament, representing the plurality if not the majority of Christians in Lebanon, and the successor to Bachir Gemayel’s Lebanese Forces militia. Gemayel was “elected” (there was no other candidate on the ballot) President of Lebanon in August 1982, with Israeli support in the wake of their invasion. Less than a month later he was assassinated, leading to monstrous reprisals from the Christian militias against the Palestinians (who, incidentally, are not thought to have been responsible for the bomb which killed Gemayel).

Tony is the owner of a car repair shop, and the level of Tony’s devotion to the cause can be measured by the fact that in the back of the garage there’s a TV which plays Bachir’s speeches on a constant loop. The second antagonist, Yasser, is a Palestinian who is working as the foreman of a construction project in Tony’s neighbourhood. Noticing that the drainage pipe from Tony’s balcony is in contravention of regulations, Yasser knocks on Tony’s door to inform him that they will need to repair this. Recognising Yasser’s Palestinian accent, Tony becomes obstreperous instead of rationally accepting the request, and slams the door on him. Yasser’s team then proceed to fix the drainage pipe in any case, and Tony comes to the balcony and smashes their new pipe with a large mallet. At this point Yasser, understandably enough perhaps, calls Tony a fucking prick.

The court case begins after Yasser’s boss tries to smooth things over, first by taking an extravagant-looking box of chocolates to Tony’s pregnant wife, and then by asking Yasser to “apologise” to Tony for the insult of calling him a prick. Yasser is a proud and somewhat stubborn man, but is in no position to argue, because his status is very precarious. 70+ years after the Nakba, Palestinian refugees still have no legal status in Lebanon, other than that of refugee assured by international law. They are not legally entitled to vote or work in the country. As such, Yasser is working off the books, which is why he cannot say no to his boss’s request. As they arrive at Tony’s garage, Yasser gathers himself to make the apology, but doubles back when he sees the TV showing footage of Gemayel speaking against the Palestinians. His boss then tries to bring him back, but Tony pushes things over the edge by telling Yasser that he wishes Ariel Sharon “had wiped you all out”. Further discussion of this in the accompanying post, but the upshot is that Yasser then punches Tony and breaks two ribs. And thus commences the case. I’ve already given away a little bit more than you see in the trailer, but not much at all, as everything that I’ve described happens within the first fifteen minutes of the movie. Watch the trailer now, and then watch the film.

As memtioned in the previous post on Costa Brava, Lebanon, Lebanon never had any such thing as a Truth and Reconciliation Commission after the Civil War. This film, made by the same director as West Beirut, nineteen years apart, may be seen as an attempt to bridge that gap. The acting is amazing. I learned after watching that Adel Karam, who plays Tony, is a bit of a superstar in Lebanon. He packs out the Lebanese version of the O2 or the Apollo with his standup comedy, and is to be seen in at least one more of the films that I will eventually cover on this blog. Kamel El Basha, as Yasser, is *understated, *in perfect balance with Karam’s overstated.

Memory Box (2021) does essentially the same thing as The Insult, but the vehicle for the memories here is not an angry courtroom. It’s a box. A box of memories, like it says. Maia and her daughter Alex live in Montreal, and Maia’s mother also lives nearby. On Christmas Eve, Alex is at home with her Teta (grandma) when a delivery guy comes round with a very large box, addressed to Maia. Alex’s grandma immediately tells the man to take it away, confusing Alex ten-hundred-fold, but Alex of course tells the man that her grandmother is mistaken, and signs for the box. Teta then insists on hiding the box behind the door leading to the basement, and inevitably later that evening, when Maia has returned home, the box tumbles down the stairs, and empties out all its contents.

Alex of course wants to know what’s in the box, but Maia resists and Alex has to find out by surreptitious means. And that’s all in the trailer, anyway, so just look at that, I guess. This isn’t a technical appreciation, but I’ll say that I loved the creative effects in the movie, by means of which the past is brought so vividly to life in the present. You can already see a bit of this in the trailer. The plot of the movie - this is not a spoiler - is that beginning in June 1982, at the hubristic moment when Christians might have thought that they were about to “win” this god awful war, things go downhill for them very quickly. It’s pretty much the same scenario as West Beirut. I suppose that the only difference is that this gradual deterioration and eventual devastation of daily life happened to Muslim areas much earlier on in the war. Once the Christians were abandoned, from 1983 onwards, by their erstwhile Israeli allies, fighting broke out within the Lebanese army, which divided into factions, and Christians were now hemmed in by Syrians, resurgent Druze and newly empowered Shi’a militias aided by Iran. By the end of the war things were so confused that Christians were fighting against other Christians, and indeed Muslims were also fighting against each other, already jockeying for power in the post-war state that they saw coming. As with West Beirut, though, this film is absolutely not about the politics. It’s only about the disaster that the war brought on all these poor ordinary Lebanese people.

Concluding paragraph - Who did win the Lebanese Civil War, if it wasn’t the Christians or the Palestinians? Israel, maybe?? They got the PLO out of Lebanon, right??? So that must have been the end of all their troubles, surely???? Well….. I’ve got another post all about that, as previously mentioned, too many times already. Read that if interested. And I suppose that I may well at least partially have dropped an answer to the question in the previous paragraph.