Occupation *Annexation #0

* Edit (26/9/25): I changed the keyword title of this article from “Occupation” to “Annexation” in acknowledgement of what is now being more or less openly admitted in front of our eyes, and was previously denied, however implausibly. I’m leaving the previous title, crossed out in red, for rhetorical effect (in case it’s not obvious, which it should be, and sorry if I’m overexplaining).

Another hiatus. I had set myself the task of getting to Iran via Lebanon, and back to the heart of this whole matter, by Purim. Read chapters 11 and 12 for all the detail on that. I made the deadline, thanks perhaps to a certain amount of OCD, but promised myself a proper break after that. I haven’t been resting too much, as I wanted to try to get through all the Israeli and Palestinian films about the occupation of Gaza and the West Bank (the ones which I have been able to find, at least - a few of them have eluded me). Even as a passive watcher, I’m feeling a little bit saturated, so writing a “proper” post can wait a week or two. Hardly surprising that I’ve got a certain amount of indigestion, having just passed one hundred films in the last week 😵

In the meantime, I’ve added a few features to this blog. I created a chapters page (link in the menu above) and two pages for actors and directors of the films on the lists. I’m not listing the director of every single film. I’ve just included the ones who have made at least one completely jaw-dropping film. In fact I haven’t been able to include everyone who deserves to be there, because the information isn’t always so easy to find. As for the actors, I haven’t counted them according to whether they have a major role in the films that I list them in. Sometimes they’re only in small walk-on roles, but the fact that the same people keep turning up (most especially in the case of the Palestinian actors) indicates that they operate in quite small circles. Hardly surprising, of course, in both the Israeli and Palestinian cases.

Something else that needs to be mentioned about the Palestinian actors on that list - I’m pretty sure that every single one of them comes from the Israeli side of the 1948 armistice lines. That is to say, they are Arabs born on that side of the line after the State of Israel came into existence, which makes them citizens of the state, albeit citizens whose agency within the State is very obviously circumscribed compared to a Jewish citizen. Still, as Israeli citizens, they’re at least free to move around and make films where they choose. A freedom accompanied with great responsibility, in the sense that they must represent the voices of those on the other side of those 1948 lines, who of course have nothing like the same freedom of manoeuvre. One of the Palestinian actors on the list, Maisa Abd Elhadi, became the subject of quite a big controversy after the Hamas attacks of 7/10/23. Emotions are very high indeed, so I’m not going to comment on the story itself. Read and decide. What you decide will inevitably depend on your starting point. I only cite this as evidence of the very peculiar position that these people are in. Another example of this ambiguous and precarious position, which I thought I had already mentioned, but perhaps not in fact. is Saleh Bakri, whose first feature film appearance was in 2007 in The Band’s Visit (a very nice Israeli production which I will definitely talk about at some point), but who in 2013 announced that he would no longer participate in the Israeli film industry, in protest at the “increasing fascism” in the country. I wonder which younger brother of a heroically martyred paratrooper was Prime Minister at the time that Bakri took that decision.

They represent the full range of the Palestinian experience. Two of them, Zoabi and Abu Assad, were born and raised on the Israeli side of the 1948 ceasefire line, while the others were raised either in the occupied territories or in the Palestinian diaspora (or indeed both). There’s very little sugar-coating in any of their movies, but having said that I do have to declare a special fondness for the one full-lenth movie which Sameh Zoabi has so far produced. Tel Aviv on Fire is the most extraordinarily uplifting piece of work - the only film out of any that I’ve seen on either the Israeli or Palestinian side of this story that manages to find humour in the midst of the darkness and despair. It’s not even too far over on the bitter end of the bitter-sweet scale. And I really appreciate the acting style of Kais Nashef (it really ought to be Qais, but they always write “Kais”). I already mentioned him in my lamentably short post about Habibi. Needless to say that I’ll definitely be writing about Tel Aviv on Fire at some point. It’ll be a good excuse to rewatch it once or twice.

Wait, it’s not true that there’s only that film which finds humour in the situation. There was one amazing short film that I found on Netflix, called Ave Maria. No point telling y’all what it’s about, other than that it presents a strange encounter of silent nuns and Jewish settlers. That doesn’t sound like a recipe for comedy, but trust me to tell you that they pulled it off. No more spoilers. It’s only fifteen minutes of your time to go away and watch it.

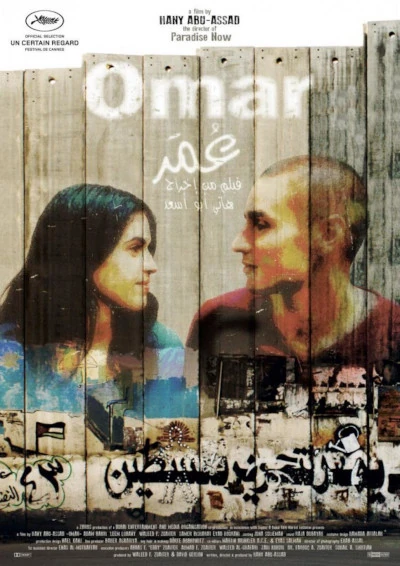

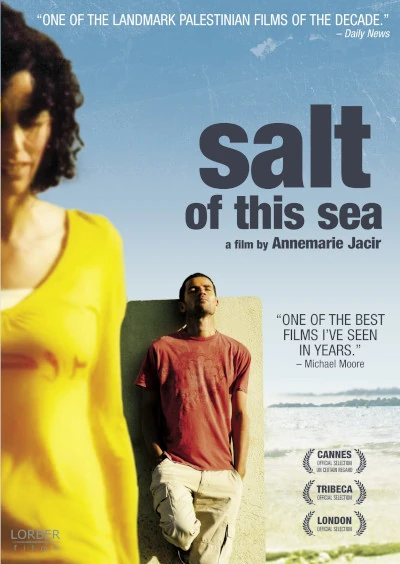

I guess I’m also being a bit unfair not to credit Annemarie Jacir with a fair bit of humour in her films, especially in Wajib, which I’ve already written about, but it’s not always humour that gets you through a film anyway. Sometimes it’s pure adrenalin. And the standout director for that among those listed here is Hany Abu-Assad. Omar was one of the first movies that I watched while I embarked on this odyssey, and my God was I ever so much on the edge of my seat watching a movie? Whichever side of the wall your sympathy falls, you’ll be gripped by the thriller. Paradise Now is equally enthralling, albeit not at quite the same breakneck speed and actually rather contemplative in a horrifying way.

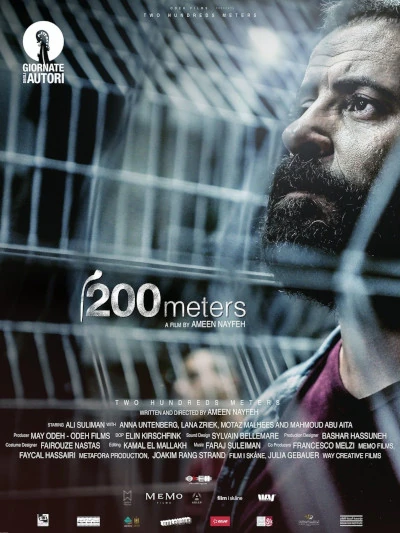

Ameen Nayfeh’s films feel quite close in spirit to Jacir’s - being focused on the intolerable disruption of the occupation to ordinary people’s daily lives and means of survival. They show the many ways that any individual can get caught up in the vortex, without having looked for the trouble. His very short film The Crossing has one of the most amazing moments of prolonged awkward silence that I’ve ever seen in cinema, and his first feature 200 Metres is all about a guy who has to go to the ends of the Earth to get to a place that is only 200 metres away as the crow flies. Anyway, no spoilers - you can find it on Netflix (in the UK, at least, but hopefully wherever you are as well). It’s actually a *bit *of a thriller, but not in the hardcore way that Hany Abu-Assad’s films are. The themes are a bit more social than very directly political, although of course.everything in these films is political. There’s no way around that.

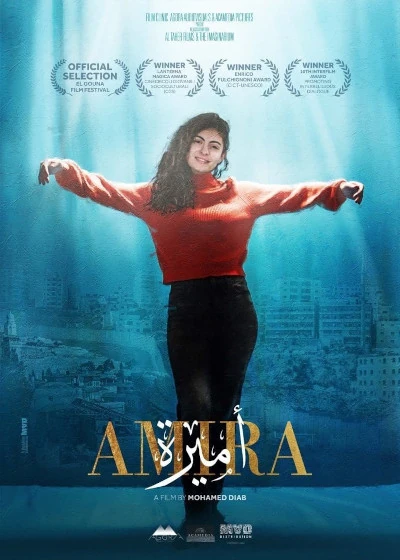

Onto more directly political themes again, Najwa Najjar’s first feature film, Pomegranates and Myrrh, is a story about lives disrupted by unjust imprisonment as a direct result of resistence to illegal settler activity. It got a lot of criticism from the Puritans for showing an honest picture of the loneliness and the dilemmas of the wife of an arbitrarily imprisoned man. Honestly I couldn’t see what the hell she’d done wrong, but then again I’m a decadent Westerner, so what do I know? An even greater controversy met Amira, which was directed by the already well established Egyptian director Mohamed Diab. For sure, if Pomegranates and Myrrh upset a few people, I can see that Amira caused them to blow gaskets. No spoilers. Let’s just say that it takes the scenario to the extreme. If I learn one day that that film is in any way based on a true story, my mind will trip a fuse.

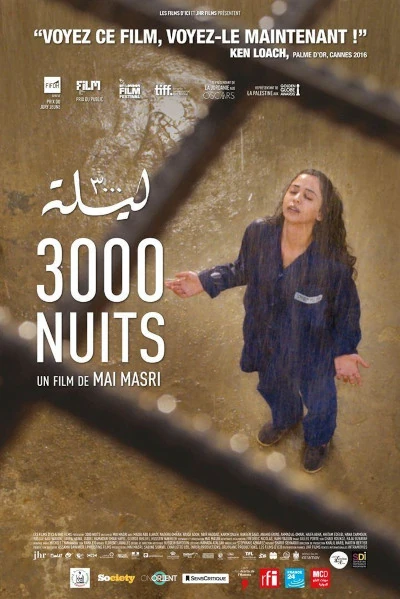

Last one of those six to mention - Mai Masri, whose feature film 3000 Nights is likely to be coming up in my next post, so I won’t say much about it. Like the two films mentioned in the preeeding paragraph, it’s about the life of Palestinians within the Israeli prison system, but unlike those two it’s the prisoner who is at the centre of this one. I’ll be watching it again before that next post, so I’ll leave it there for now. Masri is also the director of two documentaries on my list about Palestinian exiles in Lebanon. But exile is another subject. I’ll get round to that next time I circle back to Lebanon. When I get to that, I’ll certainly have a lot to say about the films of Mahdi Fleifel.

You certainly wouldn’t expect any decent Israeli or Jewish director to go into this situation looking for humour. There’s little to be had. For any Israeli with a conscience there’s only anguished soul-searching. Here are a few significant names:

I’ve already looked at the work of three of them. Yaron Zilberman was the director of Incitement, about which I wrote a good 3K words (“good” meaning “at least” - you decide if they’re worth reading). That’s certainly one of the most chilling of these films, simply because it’s about events which were all too real, alas. It was slightly remiss of me not to mention Zilberman in the post, but to be honest I didn’t initially find a lot of information on the making of the film, and anyway I very freely admit that these movies are more often than not a springboard for me to go off down historical or geopolitical alleys, and Incitement provided a loooooong Hansel and Gretel trail of cake crumbs to follow down those alleys. Zilberman was, by the way, the director of a completely different piece of work - A Late Quartet, which some more classically minded types may have seen. Philip Seymour Hoffman was in it, and please let me know if you’ve seen him in a bad film. I haven’t, and if such a thing does indeed exist, A Late Quartet certainly wasn’t one of them.

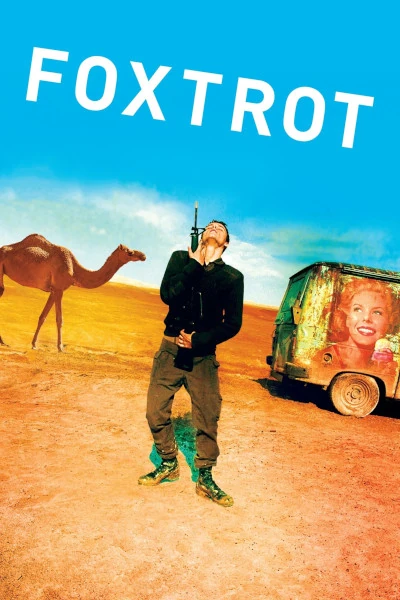

Samuel Maoz and Joseph Cedar are the two other Israeli directors whose films I’ve written about already, both of them in the post about Israel’s Lebanon War. Maoz was a rookie tank gunner during the 1982 invasion, and his 2009 film Lebanon is very obviously based on his direct personal experience. I don’t know if his 2017 film Foxtrot is similarly based on personal experience. If not his own experience, it is of course an experience that every Israeli knows. Spoilers needed? It’s about losing a loved one in the endless war, but the difference from Palestinian films which of course deal with the same issue is that Foxtrot is totally surreal, and honestly I’m still thinking three or four months later what it was all about. Don’t let that description put you off. It’s a great film - it just needs to be watched a couple of times. Maybe even then it won’t entirely make sense, and maybe that feeling of confusion and disorientation is entirely the director’s intention.

Joseph Cedar’s Beaufort was another film discussed in the aforementioned post about Lebanon. He’s got a couple of films about the occupation, and what he very much adds to the discussion is the fact that he comes to the subject from an Orthodox Jewish perspective. Some readers will of course find this very controversial (to put it mildly), but the fact is that prior to making the first of his two films about the Occupation he spent two years living on the settlement of Dolev, approximate ten miles northwest of Jerusalem. I have no idea at the time of writing as to whether he went there as a true believer in the settlers’ ideology of territorial redemption, or whether he always intended it as deep level research for his film work. All I can say, regardless of that question, is that his first feature film, Time of Favour (aka HaHesder - The Arrangement - ההסדר) is a movie that gets under the skin of the settler movement. I’m sure that it’s not critical enough for the liking of many, but I think that a critique of the whole enterprise is very clearly implied, if not openly stated. It does very obviously come across sometimes as having been rather low budget (fair enough - it was his first feature), but that doesn’t detract from the fact that it’s a bit of a thriller which touches on possibly THE most sensitive issue in the Middle East (apart from a few Sunni/Shia problems, which I’m not going to be getting into). No spoilers at all here. Apopos not very much at all, it’s now a rather faint memory, but I’m pretty sure that I caught *Time of Favour *on TV a year or two after its release. I occasionally asked myself in the subsequent years if I could find it again, and actually it didn’t take long at all to find it once I started obsessively digging for this project. By contrast (!!!!) Cedar made a second film about settler life in 2004, called Campfire, which is unfortunately very difficult indeed to get hold of where I am. At the time of writing I still haven’t seen it, which is pretty frustrating because I’ve really appreciated everything else from this guy, and I would like to see how Campfire contradicts or complements his first movie. No worries - I’ll get my hands on it eventually 😜

Another director who has seen the settlements close up from the inside, over a much longer period than Cedar (who grew up in New York and then Jerusalem) is Tsivia Barkai Yacov. She was raised in (on?) Beit El, one of the earliest settlements established by the settler organisation Gush Emunim, shortly after the watershed election of 1977. Anyone who knows a bit of Bible should recognise the name Bethel. Same place, kind of. It’s the place where Abra(ha)m pitches his tent in Genesis 12 and 13, and it appears again in Genesis 28, as the site of the Jacob’s Ladder story. Well, they didn’t pick that site completely by accident, did they? Having waited ten years for the government that would give them the green light, they’d certainly planned it all out. As far as scholarship can tell, the biblical Bethel was somewhere in the vicinity, but we may assume that it all looked a bit different back then. Barkai Yacov’s film Red Cow does not take place in/on Beit El or any similar settlement. I’m guesing that she wouldn’t have been very welcome (it’s a bit of a spoiler if I explain why). Instead most of the action is in a Jewish settler community in Silwan, an Arab neighbourhood in East Jerusalem, very close to the Old City. I assume that that choice was much more practical. Although there’s not a single Arab character in the film, it’s very much a film about the Occupation, and in fact it’s very complementary to Cedar’s Time of Favour. Not the same story, but very comparable. Red Cow is more extreme in its depiction of the settler delusion (not a delusion is you will it, I realise, but anyway….), and also in the nature of the rebellion against that. Hardly surprising, perhaps, since it’s made almost two decades later, and things didn’t get any less crazy in that period. No spoilers. No spoilers. You can watch them both, read the Wikipedia spoilers, or wait for the post in which I’ll put them together. Red Cow is in fact most probably going to pop up in more than one post, as there are other themes that it touches upon.

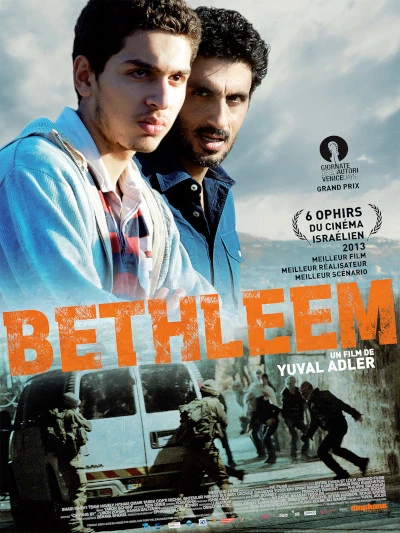

Yuval Adler is a director of thrillers, who has now carved out a career for himself in Hollywood, but his first feature film, Bethlehem, is probably the closest in comparison to the work of Hany Abu-Assad. If there’s one thing that I can say here - sorry for the spoiler - it’s not to expect happy endings in Israeli-Palestinian thrillers. Bethlehem will probably be a good choice to pair up with Omar. By coincidence they were made in exactly the same year, and there’s really quite a lot to compare in them.

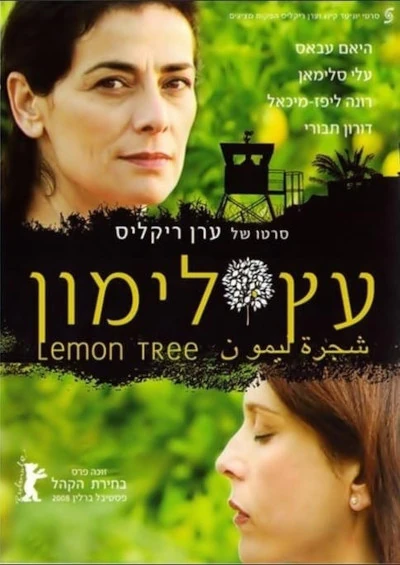

And finally - but definitely not as an afterthought - we have Eran Riklis. I actually made a “mistake” , if you want to call it that, by originally placing his films on the Palestinian side of the ledger. OK, it’s true that The Syrian Bride is rather obviously Israeli-made when you watch it properly, and even Lemon Tree couldn’t have been a Palestinian production when you really think about it. However, before going into the research about who in fact directed which film, I was totally prepared to suspend any disbelief that Lemon Tree was a film which saw the situation 100% from the Palestinian side of the fence (not the wall - I could explain, but if I elaborate on that comment it will be a massive spoiler). Likewise, A Borrowed Identity has an Arab as its main character. No doubt there are people out there who would consider this kind of film-making to be the most insidious form of Zionist colonialist oppression, wolf in sheep’s clothing, cultural appropriation, etc., and indeed his Wikipedia page does detail some controversy about him changing a crucial detail in a storyline submitted to him by an Arab/Palestinian writer, while continuing to credit him for the writing. It’s all treading on eggshells, I guess, and one thing that I’m pretty sure of is that Riklis has probably had a lot more abuse than that over the years from the blowhards on the Israeli right, in Likud and what used to be considered beyond the pale. I’ll take that as a measure of who he is, then. There’s a very early film of his called Cup Final (Gmar Gavi’a - גמר גביע), made in 1991, which I’d very much like to see, but I think it’s going to be incredibly difficult to find. Hopefully some kind Israeli reader of this blog will eventually help me out with that.

Now I’m thinking about where exactly to start. Already before writing this post, the plan was to go in hard, with a post about 3000 Nights, up against the Israeli Dror Moreh’s documentary The Gatekeepers, which consists of interviews with six men who were heads of the Israeli internal security service, the Shin Bet. Grim enough. But I suppose I could do the Omar/Bethlehem post. Let’s see which way the wind blows me.